Click on the title to listen to the episode.

41. Soccer and the 1914 Christmas Truce

At Christmas 1914, British and German troops on the Western Front left their positions, crossed into No Man's Land, and fraternised with each other. In some places, football matches were played. This special Christmas edition of 'Rugby Reloaded' explores the myths and reality of the Christmas football matches, and discusses their importance to soccer's global image.

42. The Past, Present and Future of the Rugby League Challenge Cup

The Rugby League Challenge Cup is the sport's oldest continuous tournament. But in recent years, the thrill of the cup has been declining - and now the RFL are asking overseas clubs for six-figure bonds to take part. Are knock-out cup tournaments like the Challenge Cup and the FA Cup doomed to fade away? Find out what history tells us about the future of one of British sport's most prestigious tournaments on your latest ten-minute trek through the past.

43. Ebenezer Cobb Morley and the birth of the Football Association

Was Hull-born Ebenezer Cobb Morley the 'father of football'? Not unless his child was switched at birth. Morley's rules bore little resemblance to modern soccer and his leadership of the TA was a failure. But why do we need stories about 'fathers of football codes'?

44. Refereeing & Philosophy with NRL referee Tim Roby

Rugby Reloaded plus is back - this week I'm talking to NRL and former Super League ref Tim Roby. Tim chats about his career, discusses the uses of philosophy for referees, contrasts league in Britain and Australia, talks about his experiences at the Koori Knockout Comp, and much, much more.

45. Red Star, Rumania & Eastern European Rugby

To mark Red Star Belgrade's debut in the Rugby League Challenge Cup, this week's episode looks at the history of the rugby codes in Eastern Europe, discovers what happened to Yugoslav rugby league, and investigates why Rumania never became part of the Six Nations.

46. When Six Was Four - The Roots of the Six Nations

This week's Rugby Reloaded plus chats with journalist Huw Richards about the origins of the Six Nations, its early rivalry with soccer, how Rugby's Great Split of 1895 changed the tournament forever, and much more.

47. Italy’s Other Football Code: The Rise of Italian Rugby

This week's Rugby Reloaded looks at the history of rugby in Italy and how national politics have shaped the game. From Mussolini to Berlusconi, the sport has always been seen as a way to influence society and business - and along the way it has fought its own civil war between union and league.

48. 'When Ellery Was King': Sean McGuire on the 1980s and League Expansion

Rugby Reloaded plus this week talks to Sean McGuire, former St Helens' CEO and London rugby league pioneer. Sean chats about his experiences in London in the 1980s with the Hornsey Lambs and reflects on what that means for the future of rugby league, opportunities for expansion, and the never-ending thrill of the game.

49. French Rugby League: ‘The Struggle and the Daring’ with Mike Rylance

This week's 'Rugby Reloaded plus' chats with Mike Rylance about his new book The Struggle and The Daring, just published by Scratching Shed. We talk about the history of French rugby league, its fabulous origins, ban by Vichy, the post-war struggles, immortal sides of the 1950s, and its fall from grace.

50. 100 Years since the King's Cup - but was it Rugby's 'first world cup'?

This week sees the centenary of thekick-off the 'King's Cup', the international military tournament that celebrated the end of World War One. But was it really 'rugby's first world cup' as some claim? As this week's podcast discovers, it was not a world cup but something far more interesting and complex, which shaped the future of international rugby union for the next fifty years.

51. 'Numbering Up' Statistically speaking with the Rugby League Project

This week's 'Rugby Reloaded plus' interviews Andrew Ferguson, one of the brains behind the 'Rugby League Project' website, which aims to compile a complete database of the game's statistics. We talk about where the Project gets its stats, the problems of assessing matches, and why there are no unified records for the sport - not to mention swapping notes on ganglions, the old-school researcher's curse.

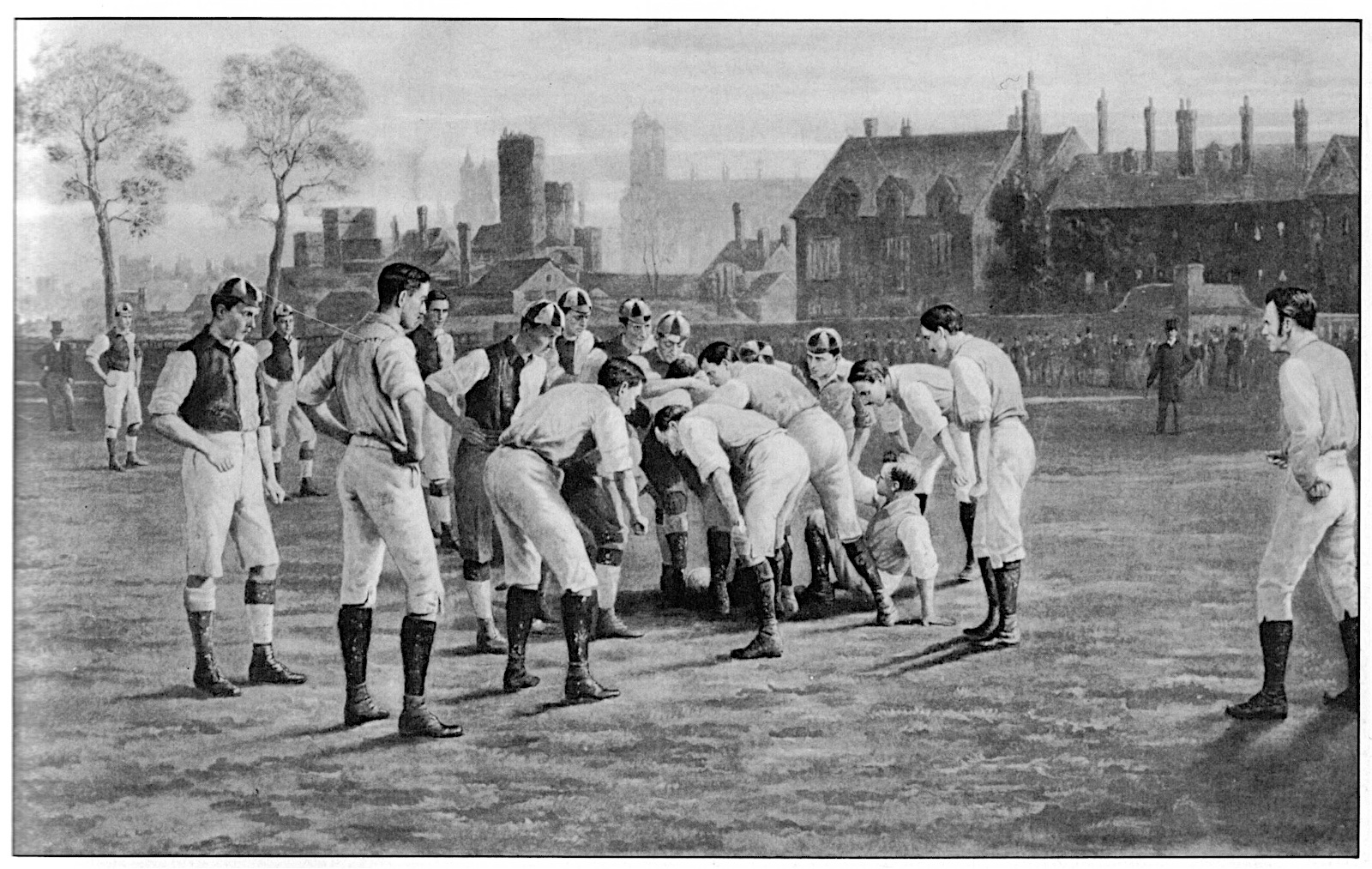

52. A Short History of the Scrum

The shape of things to scrum? This week's 'Rugby Reloaded' looks at the past, present and future of the scrum. Take a ten-minute trip back to the time when scrums worked the wrong way round and discover why the scrum's problems have always been a headache for all codes of the oval ball game.

53. Rugby Union’s 50-22 proposal and the Evolution of Union and League

This week we take a deep dive into the announcement that rugby union may introduce a 50-22 rule modelled on rugby league's 40-20. Is it another case of union stealing league's clothes? This week's ten-minute rugby time tunnel looks at the evolution of rugby rules and asks if it is inevitable that union will go down the same road as league.

54. 1906: The Year That Changed the Oval World Forever

1906 was the year league went 13-a-side, the All Blacks transformed rugby union, and America football legalised the forward pass. Discover how 1906 revolutionised the Oval World in the new ‘Rugby Reloaded’ podcast.

55. The American RL All Stars & lessons for today with Gavin Willacy

This week's 'Rugby Reloaded' plus talks to Gavin Willacy, author of No Helmets Required about the incredible story of the 1953 American All Stars tour of Australia. We chat about how it happened, why its promise failed to materialise, and what lessons can be learned as rugby league once again discusses expansion into North America. (With apologies for the poor sound quality on this episode)

56. Game of Throw-ins: A History of the Line-Out

This week we step in the ten-minute time tunnel to look at the history of the line-out in both rugby union and rugby league. The throw-in from touch is one of the few common rules remaining in soccer and rugby union, so we trace its evolution, discover why league abolished it, and consider what the future holds for it.

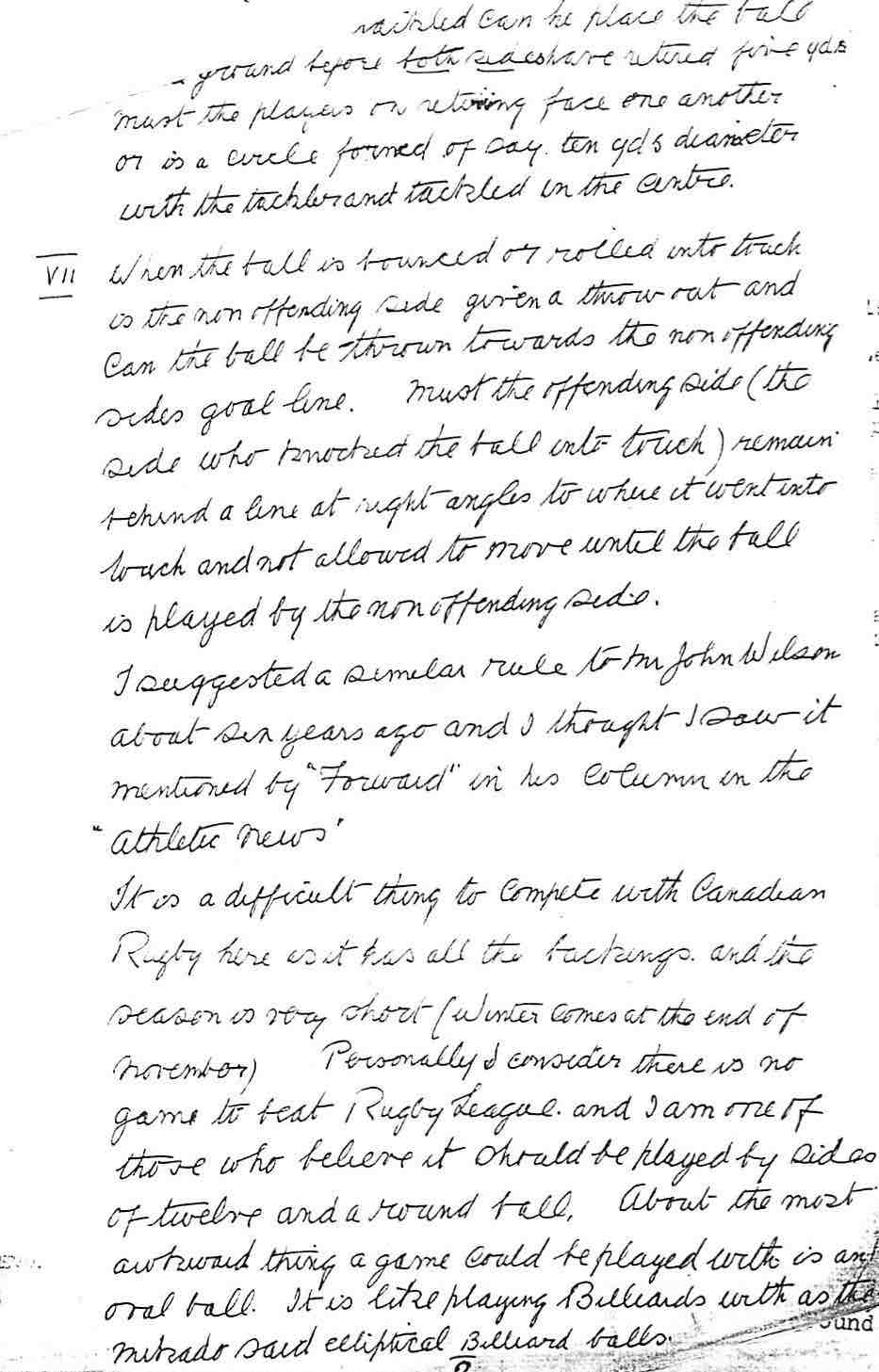

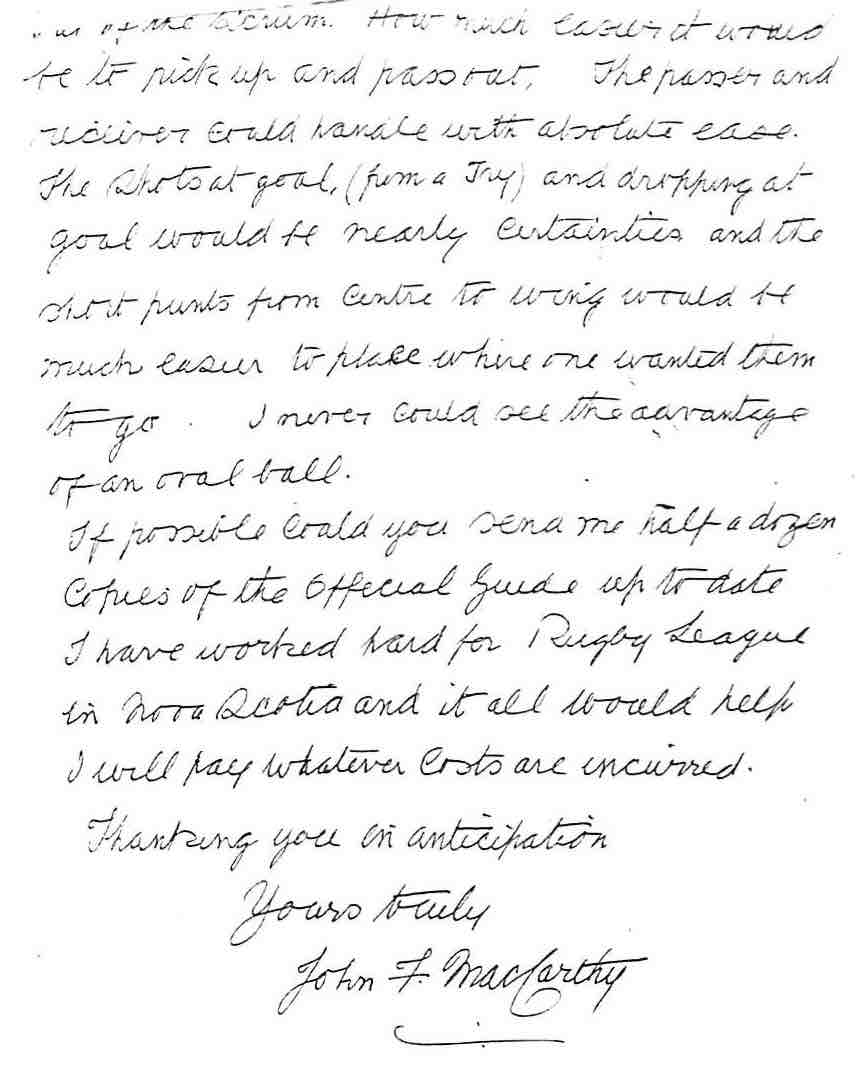

57. Before the Wolfpack: A History of Rugby League in Canada

The Toronto Wolfpack kick-off their home season on Sunday, and so this week's 'Rugby Reloaded' travels back in time to unravel the forgotten history of rugby league in Canada before the Wolfpack. It's a tale of heroic pioneers in the 1930s and missed opportunities in the 1950s…

58. Argentina: Why Soccer Defeated Rugby

In Argentina today, soccer is without question the passion of the people. Yet in 1900 soccer and rugby were equally as popular - so what happened? How did rugby lose out to soccer? This week's ten-minute time tunnel examines how social and political changes in Argentina not only changed the nation but also transformed sport, leaving rugby the sport of Argentina's social elite.

59. Rugby in Asia and the Far East

Why was there no rugby in India? And why is rugby in Sri Lanka one of the sport's best kept secrets? This week's ten-minute time trek through rugby history examines the game in Asia and the Far East, looking at how China, Malaysia, India and Sri Lanka reflected both the past and the future of rugby union.

60. Hybrid Heaven or Merger Most Foul? When Aussie Rules voted to merge with Rugby League

Rugby league and Aussie Rules to merge? Gridiron fusion with Aussie Rules? It could never happen - but it has, or at least been attempted. This week's 'Rugby Reloaded plus' sits down with Spencer Kassimir to explore the times when rugby league and Aussie Rules sat down to create a hybrid game, discover the World War Two game that brought together the best of the NFL and the VFL, and chat about the International rules AFL-GAA games.

![Syd Gaunt [bottom right], Canadian rugby league pioneer, amid the burnt-out wreckage of Rochdale Hornets' stand in 1935. ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/502784a984ae2d2eef45097c/1500723123453-3WHT824TXZA6DDNW8XXH/image-asset.jpeg)