-- This is an extract from 'The Tyranny of Deference: Anglo-Australian Relations and Rugby Union before World War II' published in Sport in History in 2009. It deals with the origins of the rugby union rivalry between England and Australia.

Although in the 1850s the founders of Victorian (later Australian) rules football took their inspiration from the football that was played at Rugby School in England, it wasn’t until 1863 that a club which actually played the Rugby School code of football was founded in Australia, Sydney University Football Club. Over the next three decades New South Wales and eventually Queensland adopted Rugby football as their primary football code. In 1874 the Southern Rugby Union (SRU) was formed in Sydney as the governing body of the game in Australia. From its inception, the sport was closely associated with the universities and the Great Public [i.e. private] Schools. By the late 1890s, however, rugby had become a mass spectator sport in the eastern states, attracting considerable crowds, press coverage and public interest.

Part of its appeal among all classes was the opportunities it offered for competition between different countries of the Empire. As with cricket, the growth of rugby brought with it regular tours from teams representing New Zealand and, most importantly, Britain. In 1888 an unofficial British rugby tour organised by the sporting entrepeneurs Alfred Shaw and Arthur Shrewsbury had given added impetus to the popularity of the game. Rugby also presented an important an important form of cultural exchange, as young middle-class Australian males took up studentships at Oxford, Cambridge or the London and Edinburgh medical schools. Indeed, a number, such as C.G. Wade and S.M.J. Woods , even represented England or Scotland at international level.

Rugby thus became an important part of the imperial sporting network that included cricket, rowing and athletics. As with these other sports, the goal of rugby tours was to use sport to generate a sense of imperial unity. Welcoming the 1904 British rugby team to Australia, J.C. Davis, Sydney’s leading sports journalist of the time, encapsulated this when he wrote that sporting tours created ‘an extended feeling of appreciation and racial sympathy. They have incidentally shown to the muscular Britisher at home that the Britisher abroad and his sinewy colonial descendents are not aliens because thousands of miles of sea intervene.’

It was in this spirit that the governing body of English rugby, the Rugby Football Union (RFU), organised the first official rugby tour to Australia by a British representative side in 1899. Captained and managed by the Reverend Matthew Mullineux, the tour proved to be unexpectedly controversial. Mullineux was disappointed with the spirit in which the Australians played the game. Most of all, he was horrified by the widespread, and well-founded, rumours that players received money for playing, contrary to the amateur regulations of the sport.

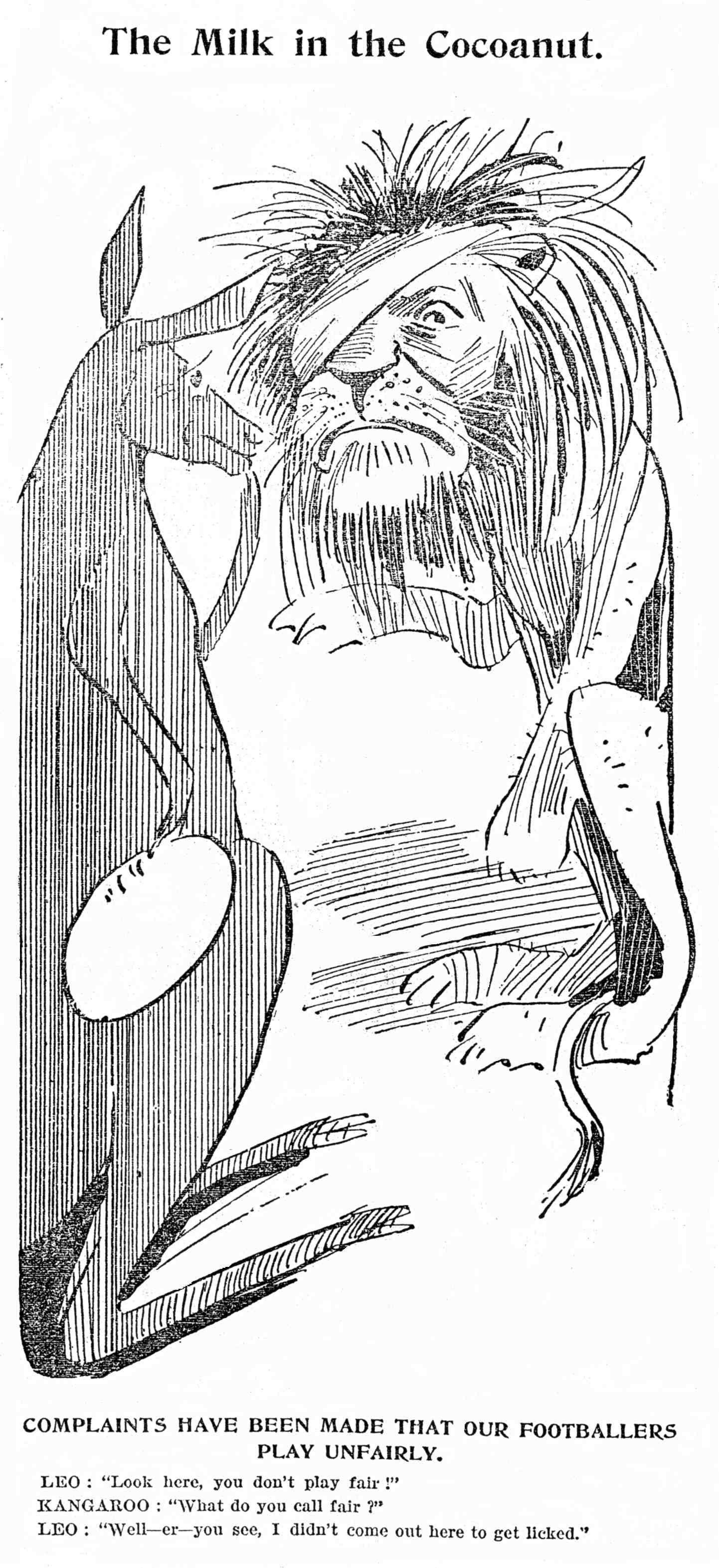

For their part, the Australians felt let down because, contrary to expectations, the British team was not truly representative; only seven of the twenty-one players in the side had ever appeared in an international before. Most importantly, they were somewhat shocked at the highly competitive manner in which the British played the game. Much to their hosts’ surprise, the British tourists appeared to go all out to win, rather then to play the game for its own enjoyment, as would be expected by representatives of the home of ‘fair play’. The contrast between the rhetoric and the reality of British play was highlighted in a newspaper cartoon published during the tour, in which a British lion confronted a kangaroo:

Lion: ‘Look here, you don’t play fair!’

Kangaroo: ‘What do you call fair?’

Lion: ‘Well-er-you see, I didn’t come out here to get licked.’

Far from being temporary hiccough in international rugby relations, these problems were exacerbated during the next British tour of Australia in 1904. Captained by Scottish forward David Bedell-Sivright, the side departed Australia unbeaten before going on to face sterner opposition in New Zealand, but left a trail of controversy behind them. Foreshadowing Douglas Jardine, the captain of the 1932-33 English cricket tourists, much of the ill-feeling of the tour was generated by the behaviour of Bedell-Sivright, about whom it was said ‘his conception of football was one of trained violence.’

Two of the three test matches were punctuated by brawling between the British captain and his Australian adversaries and a match in Newcastle against Northern Districts was interrupted when he led his men off the field in protest against the dismissal of British forward Denys Dobson. The referee alleged that Dobson had sworn at him after being penalised at a scrum. Bedell-Sivright denied that one of his men would do anything so low and promptly marched his side off the pitch. Eventually they were persuaded to return, but the incident became notorious as another example of the ease with which the British dispensed with their principles of fair play when it suited them.

The relationship deteriorated further during the first Australian rugby union tour of Britain in 1908. Following in the wake of successful tours ‘Home’ by the New Zealand and South African national sides, the tourists - known as the Wallabies - were dogged by controversy and deteriorating relations with their British hosts. The Scottish and Irish rugby unions refused to play them because of suspicions that the Australians were professionals. On the pitch, the tourists were accused of being overly-violent and playing solely for the purpose of winning. Unprecedentedly, three players were sent off during the tour, including one, Syd Middleton, against Oxford University, the very embodiment of the amateur ‘rugger’ tradition.

For many in Britain, the tour demonstrated the moral deficiencies of the typical Australian. Scottish rugby writer Hamish Stuart claimed that ‘custom and the national idea have so blunted their moral sense that they are sublimely unconscious of their delinquency and are sincerely surprised when accused of unfair practice’. The Australians were reciprocally less than enamoured by their treatment in Britain. Returning home, James McMahon, the tour manager, complained that

as visitors to the Mother Country, as representatives of part of the British nation, [the players] could not understand and were certainly not prepared for such hostility as was shown them by a section of the press.

In many ways these rugby disputes anticipated the 1932-33 Bodyline cricket controversy. Like the Bodyline events, the disputes were not caused by any Australian proto-nationalism but by the injustice felt by Australians when British sides did not abide by the supposedly British sporting values of ‘fair play’ or refused to accept their opponents asequally as British as they. This was precisely the basis of much of the anger of Australians during Bodyline. It was not so much that the English cricket captain Douglas Jardine was engaging in intimidatory tactics but that he appeared to have departed from the ethical code of the British gentleman and was using such tactics against fellow Britons. This feeling of betrayed loyalty was captured by an anonymous ‘Man in the Street’ who published a pamphlet in Sydney titled The Sporting English, a scathing attack on the English in response to the 1932-33 cricket tour and its aftermath:

We Australians are at a loss to understand why we, alone of all the Empire, are singled out for these continual attacks. We claim to be loyal to the throne, and to uphold the traditions of the British race. Also we pay our debts and are England’s very best customer within the Empire. When danger threatened, we were of the first to respond to the call to arms by the Motherland.

The underlying imperial loyalty of such complaints was made explicit by Wallaby captain H.M. Moran who, despite noting that his fellow tourists had ‘developed a dislike for everything English’, also pointed out that ‘there is one symbol of [Australian] unity with the nation of nations. It is the monarchy.’

An Australian will often express himself rudely about a visiting Englishman who behaves superciliously. That is common. He will frequently hurl angry criticisms at a British government. That, he considers his right. He will even in a pet be disrespectful to a British government, though this is rare. But to the King, no man with impunity may offer insult.

Thus what was being expressed by Australians in these sporting disputes was not an embryonic form of nationalism but a thwarted Imperial loyalty. And in attempting to deal with this frustration over the next three decades, far from being driven to greater hostility towards Britain, the Australian rugby union authorities sought to bend over backwards in an attempt to appease their tormentors.