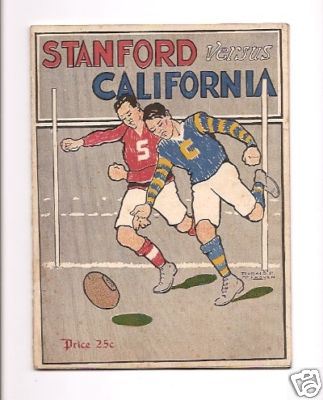

Stanford v Cal in 1914: when the Big Game was played under rugby union rules

In 1905 American football sailed into the greatest storm it had ever encountered. Since the 1890s there had been growing concerns about violence and brutality in the game. These worries came to a head in the 1905 season, when eighteen deaths and 150 serious injuries were sustained in matches. The outcry was so severe that Teddy Roosevelt - who had once said that Tom Brown’s Schooldays was one of two books everyone should read - met with representatives of Harvard, Yale and Columbia university football teams to encourage them to change the rules of the game to reduce its dangers. As a consequence, the following year the forward pass was introduced into the game.

But on the West Coast of America, disillusionment with the violence and commercialism of the American game was not so easily dislodged. Rugby had first been played at the University of California in 1882 but had been replaced by American football in 1886 as that code swept through US colleges. Now, two decades on in January 1906, the universities of California and Stanford announced that they were abandoning football altogether and taking up rugby union.

The decision to switch back could not have been taken at a better time. The triumphant All Black tourists were on their way back home from Britain and France, returning across North America - and they were keen to fly the flag in the USA for rugby and for New Zealand in particular.

Arrangements were hastily made and in early February 1906 the All Blacks arrived in northern California to play two exhibition matches against a British Columbia side from Canada. Despite being on tour for over six months, the tourists unsurprisingly romped home in both games, at Berkeley by 43-6 and then in San Francisco by 65-6. Despite the one-sided nature of the games, the press were effusive in their praise: ‘the superiority of rugby to our own amended game was demonstrated even more forcibly than at the very interesting contest of last Saturday,’ declared the San Francisco Chronicle.

The experiment was interrupted two months later when the San Francisco earthquake reduced much of the city to rubble. But support for rugby grew and California and Stanford were joined by the universities of Nevada, Santa Clara, the Pacific numerous northern Californian high schools and San Francisco’s elite Olympic athletic club. There was even talk of an American universities' rugby tour of New Zealand.

And on the East Coast, where the All Blacks had played an unofficial match against a pick-up New York team when they arrived in the US, an Eastern Rugby Union had been founded in April by three clubs. Rugby was back.

The game’s international significance was enhanced by a changing world situation. Japan’s stunning victory over Russia in their 1904-05 war meant that the Pacific Ocean had suddenly become a region of intense diplomatic interest. The Anglo-Japanese Alliance was signed in 1902, causing consternation to the newly federated Australian government, whose ‘White Australia’ policy was based on racist fears of Asian domination. The Australians sought to counter fears that the British might abandon them to the Japanese by developing links with the United States.

For its part, Teddy Roosevelt’s government wanted to demonstrate that despite Japanese success America was the dominant naval power in the Pacific. So in late 1907 it despatched a fleet of sixteen battleships on a goodwill tour of the region, calling at major ports on both sides of the ocean. In August 1908 it visited Auckland, Sydney and Melbourne. It did not go unnoticed in these cities that their guests had chosen to call this mighty display of sea power the ‘Great White Fleet’.

As part of this Australian-American courtship the 1908-09 Wallabies played three games in California on their way back from their tour of Britain in February 1909. The Australians won all three matches, but the margins were sufficiently narrow to suggest that West Coast rugby was improving rapidly.

And, despite the switch from gridiron to rugby, the ‘Big Game,’ the annual showdown between Stanford and California, showed no signs of diminishing in importance as northern California’s most important sporting event. In 1910 it staged the first example of what would become a staple of American college football, the ‘Card Stunt’, where members of the crowd held cards above their heads to form a word or symbol.

Filled with hope for rugby, that summer an American Universities team of students from California, Stanford and Nevada made a sixteen game tour of Australia and New Zealand, the first overseas visit by a US representative rugby team. Despite only winning three and drawing two matches the students were never out-classed, and the tour was considered a success by all concerned. When they returned home in August the San Francisco Sunday Call was sufficiently impressed to ask in a headline ‘Will California Produce Rugby’s World Champs?’

Further evidence for this optimism was seen in 1912. The West Coast hosted an Australian touring side. They were known as the Waratahs, rather than the Wallabies, despite the fact that six of the tourists came from Queensland rather than New South Wales, the state that had traditionally borne the Waratah nickname. They played eleven matches and lost by a point to both California and Stanford, although they played the former three times and the latter twice. Most significantly, they narrowly defeated the USA national side in its first-ever international by a mere 12-8.

But under the surface, all was not well. The Australians disliked the American approach to the game, feeling that the Californian tackling was too physical and that US players were apt to take advantage of the rules. Coming just four years after the split with rugby league in Australia, the tourists were determined to uphold the amateur ethos - and the American approach smacked too much of the professional attitudes that the gentlemen from down under had so recently rejected.

For their part, the Americans were becoming frustrated with what they saw as the domination of rugby by forward play. In 1913 California suggested that teams should be reduced to 14-a-side by the abolition of one of the forwards. From his vantage point as the ‘Father of American football’, Walter Camp mischievously informed the sporting public that the Californians weren’t even playing the best type of rugby. ‘The Northern Union game, especially in Lancashire and Yorkshire, would be a revelation to many of those who have merely seen the more mediocre play,’ he argued. ‘The men who form these teams are of excellent physique, strong and powerful, putting up a hard, vigorous game with tackling that is earnest enough to be severe’.

Matters come to a head with the 1913 All Blacks tour of California. Any hopes that American rugby ascendency would continue its upwards trajectory were brutally extinguished by the New Zealanders. In thirteen unbeaten games they scored 508 points while conceding just two penalty goals, including a 51-3 demolition of the US national team at Berkeley.

Only two sides kept the tourists below the thirty-point mark. American rugby was humiliated. Instead of promoting the game, the tour demonstrated that far from being potential ‘World Champs’ America was no more than a second-rate rugby nation. It was not a message she wanted to hear.

To make things worse, the University of California fell out with Stanford over the selection of the national team. In the midst of this confusion and demoralisation, voices began to be heard calling for a return to American football. As college football continued to grow in importance in the US, many in California felt isolated from the intense intercollegiate and increasingly nationwide rivalries of the sport.

Played by a handful of local universities and now offering no prospect of international prestige, rugby’s appeal ebbed away. In 1915 California pulled the plug and declared that henceforth it would play football: ‘from now on it will be the American game for Americans. and, best of all, for California,’ declared the Daily Californian. Stanford carried on until 1919 before accepting the inevitable. Rugby’s second chance in America was all but gone.

- - For more on the history of rugby in America, pre-order my The Oval World (published in August) and read Gavin Willacy's wonderful No Helmets Required.