New Zealand captain James Ryan receiving the King’s Cup from George V

The Rugby Union World Cup kicks off in little more than three months. I'm reprinting here a slightly updated version of an article I wrote for a conference held in Sydney at the 2003 RWC. It was subsequently published as 'The First World Cup?: War, Empire and the 1919 Inter-Services rugby union tournament' in Mary Bushby and Tom Hickie's edited collection of essays Rugby History: The Remaking of the Class Game (Melbourne 2007).

...

Between 1895 and 1914, rugby union was in a state of almost continual crisis. Rugby had split in Britain, Australia and New Zealand; the English and the Scots were permanently at loggerheads over professionalism; and the Australian and New Zealand unions were openly dissatisfied with the Rugby Football Union, the de facto leadership of the international game. But by 1920 rugby union was more united than it had ever been and the RFU was the unquestioned leader of the game internationally. The reason for this change in fortune was the activity of the RFU during and immediately after the First World War, which was crystallized in the 1919 Inter-Services Rugby Tournament.

It is widely believed that at the declaration of war in August 1914 rugby union in England immediately closed down for the duration. The reality was not quite so straightforward. Initially, the RFU believed that the game should continue. Nine days after the declaration of war its secretary, C. J. B. Marriott, instructed clubs to carry on playing where possible. However, the militaristic patriotism which had been drilled into players at school and beyond proved to be overwhelming and players flocked to the colours. By September, all club rugby union in England had been suspended until further notice.

But the sport quickly re-emerged as an important military game. By early 1915 something like a structured season had developed for military rugby union teams in the south of England and in 1916 the huge influx of troops from Australia, New Zealand and South Africa into Britain saw the sport enter what, were it not for the circumstances of its playing, could be termed a golden age of domestic competition. Crowds of seven or eight thousand people were not exceptional for matches involving the teams from what were known as the white ‘Dominions’ of the British Empire.

Despite being in the midst of war, tensions between the RFU and sides from the Dominions did not diminish. The 1905 All Blacks, although widely admired for their skills were widely suspected of being professionals - thanks to receiving a three shillings a day allowance while on tour - and of not playing the game in the right spirit. Many of the 1908 Wallabies could not wait for their British tour to end, thanks to the snobbishness and widespread suspicion among English rugby union commentators that they too were professionals. Only the South Africans were unambiguously welcomed to Britain, in 1906 and 1912.

These tensions reflected the changing political relationship between Britain and the Dominions. The war brought to the fore friction between the imperial centre and its periphery, especially Australia, which were most powerfully symbolised by the narratives surrounding Gallipoli. At government level, it had amplified the tendency towards Dominion self-assertion, if not self-government. At the 1917 Imperial War Conference the Dominion prime ministers called for full recognition of the Dominions as ‘autonomous nations of an Imperial Commonwealth’.

The RFU was keen to play a role in closing these imperial fissures. As a supporter spelled out in The Times in February 1919, rugby ‘is not only national but imperial; it is the game of the most rigorous of our colonies; it is the game of the Army that has won the hardest and grimmest of all our wars.’ The prestige which it had gained during the war and its close identification with the war effort - highlighted by the number of England internationals who were killed in the war - gave the RFU both tremendous self-confidence and authority when the war ended in November 1918.

The Kings Cup unveiled

This authority was consolidated in March and April 1919 when, apparently at the request of the War Office, it staged a sixteen match Inter-Services Tournament featuring representative sides from the Dominions and the services which became known as the ‘King’s Cup’. The tournament - which was the biggest international rugby union tournament staged anywhere in the world until the sport’s first world cup in 1987 - was explicitly designed to capitalise on the popularity of services rugby union during the war years, and became a celebration of rugby union’s past and a signal of future intent. It also had a broader, political motive, as The Times rugby union correspondent noted in March 1919:

It is a most practical means of continuing and strengthening the bonds of interest between us and our relations scattered over the world. War has brought all parts of the Empire closer…. Often in the past the ties between this country and the colonies have been slender, and the strongest of them is the common interest in British games.

As well as the Mother Country, the participating teams consisted of Australia, New Zealand, the Royal Air Force, South Africa and Canada - who were there for ‘missionary’ purposes to popularise the game in North America - competing in a league table with matches being staged across Britain at Swansea, Portsmouth, Leicester, Newport, Edinburgh, Gloucester Bradford and Twickenham, which staged six matches, including the final play-off.

Despite having ‘Boy’ Morkel, the star of the 1912 Springbok tour of the UK available, the South African side was described as no better than an average club team. The three strongest sides were New Zealand, the Mother Country and Australia, with the first two finishing on top of the table with one defeat each. A play-off match was arranged at Twickenham to decide the winners and in a tight game, the New Zealand forwards came out on top, scoring two tries to defeat the Mother Country 9-3, in front of an audience which included the NZ prime minister William Massey, who was in Europe for the talks on the Versailles Treaty.

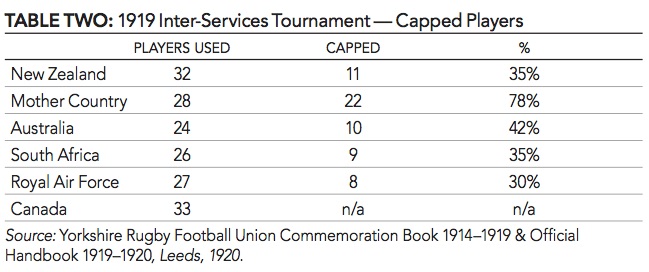

Why was the British side called the ‘Mother Country’? As RAF captain Wavell Wakefield explained in his 1927 book Rugger, the original idea had been to field Army, Navy and Air Force sides but the Navy withdrew because it felt that it could not raise a competitive side, so the army became the Mother Country. There were some grumblings about the name of the side in the press, but the arrangement meant that Britain fielded the strongest possible side, as is shown by the table of players who were either capped or who would be capped in each side.

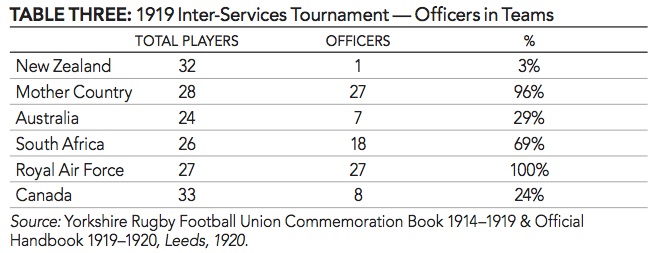

It is also revealing to examine the social background of the teams. Just before the tournament began, the Army and the Navy had discussed whether only officers should be allowed to play for their sides - as was the case before the war - and had decided that all ranks should be allowed to play. In the British armed forces, until late 1917 officers were exclusively drawn from those attending private schools or universities. However, despite the formal decision, of the twenty-eight Mother Country players, only one, the Welsh forward Ivor Jones, was not an officer. He was a sergeant-major. Every member of the RAF side was an officer, although their full-back Billy Seddon had an interesting past.

Unwelcome Guests?

The case of Billy Seddon is intriguing because he was the only rugby league player to play in the tournament for the British sides, scoring the winning four point drop-goal in the RAF’s 7-3 win over Australia. Seddon’s presence may seem surprising at first, given rugby union’s rigorous exclusion of league players from its ranks, but in 1916 the RFU had lifted its ban on league players in the armed services for the duration of the conflict. Military rugby teams with league players came to dominate the game in the war years, none more so than London’s Grove Park Army Service Corps side, led by Great Britain captain Harold Wagstaff and composed of a number of league internationals and leading club players.

The ban on league players was immediately reimposed by the RFU at its first meeting following the Armistice but a dispensation was allowed for players still in the forces but not yet playing for their league clubs. Despite this concession, not a single league player was chosen by the Mother Country. Seddon slipped through the net because, thanks to his skills as an engineer in the RAF, he had been promoted to lieutenant in 1918 (one of only a handful of league players to be commissioned), and also because he had a powerful champion in Wavell Wakefield, the captain and driving force of the RAF side, although it was admitted in the press that there had been ‘some slight qualms’ about his selection.

However, the Australians had no qualms about including several rugby league players. Rodney Noonan in 2009 article 'Offside: Rugby League, the Great War and Australian Patriotism’, published in the International Journal of the History of Sport (vol. 26, no. 15), discovered that five league players turned out for the Australian side. North Sydney’s Tom Stenning scored Australia’s try in the 6-3 loss to the Mother Country and converted a try in the 8-5 win against South Africa. Eastern Suburbs’ Jack Watkins, Newtown’s Joe Murray and Newcastle’s Tom Quinn also played for Australia but the most notable player was Glebe’s dual international Darb Hickey.

It is also noticeable that the tournament did not include the French - who had been accepted into what became the Five Nations in 1910 - despite the fact that there was by this time a considerable amount of rugby being played in post-war France. The RAF team had even undertaken a short tour of France before the competition kicked off as part of its preparations. The reason for their non-inclusion was because the tournament was entirely about cementing the links of the Empire. The French were not welcome into this private imperial party. However, they were promised a game against the tournament winners at Twickenham, which New Zealand won 20-3. A return match in Paris was also played, the NZ side winning 16-10.

In fact, this latter Twickenham match was possibly a greater imperial celebration than the tournament final. The Times reported that ‘it was more than a mere football match; it had more the character of a national festival at which the presence of the King and his four sons, Sir Douglas Haig, Sir Henry Wilson [chief of the Imperial General Staff], the French Embassy staff and the High Commissioner for NZ gave a special significance. … it was a true ‘Victory’ match.’ George V was a keen follower of rugby and a regular attendee throughout the 1920s at Twickenham. Before the kick-off the King presented the New Zealanders with the Inter-Services Tournament cup. This match was also the occasion of possibly the most overwrought use of rugby as military metaphor. The speech of Major-General Sir C.H. Harrington, deputy chief of the Imperial General Staff ridiculously described Sir Douglas Haig, General Pershing and the King of the Belgians as ‘loyal and unselfish three-quarter backs ‘ during the war.

The RFU Vindicated

Despite the triumphalism of the tournament, friction between the British and the Australians and New Zealand continued. As was the case before the war, many in the RFU felt that the Antipodeans were too vigorous in their play and did not share the required spirit of sportsmanship. Matters came to a head when the Mother Country played Australia at Leicester. The Australians’ wing-forward play was felt to be blatantly obstructive and, for possibly the first time at a representative rugby match in Britain, the crowd started calling for the referee to send off the offending Australian players. Fearful of taking such a drastic step (no player would be sent off in a representative match in England until All Black Cyril Brownlie was dismissed in 1924 against England), the referee tried to defuse the situation by putting the ball into the scrum himself. (Ironically New Zealand were to propose this as amendment to the rules in August).

Despite these points of friction, the King’s Cup cemented the RFU’s authority over the sport which it had gained due to its perceived blood sacrifice during the war. Later in 1919 it was able to dismiss Welsh calls for minor reforms of the amateur regulations and also the more wide-ranging reforms of the rules and amateurism proposed by New Zealand. Indeed, it was able to state unequivocally that any attempt to unilaterally amend the amateur regulations by rugby-playing nations would bring only one result: “severence”! The tournament also demonstrated the deep-going links between the game and the British imperial elite; no other sport, not even soccer, which was immeasurably more popular than rugby, could command the support of the monarchy, the army high command and the leaders of the Dominions.

But despite its success and the high profile it gave rugby union across the empire, the tournament was never to be repeated. Although the RFU had no great love for league competitions or argumentative colonials, the key reason for its consignment to history is obvious. The King’s Cup had fulfilled one of the RFU’s most cherished desires: it had established rugby union as the uncontested winter sport of the British Empire.

- - For more, my soon-to-be-published The Oval World: A Global History of Rugby will look at the tournament in its wider context and its implications for the future of rugby union,