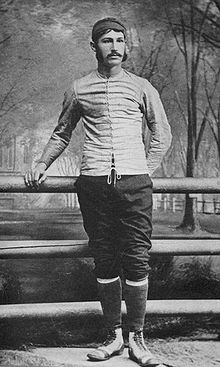

A brief glimpse of his career should be enough to convince anyone of his greatness. He made his debut for England in 1887 at the age of nineteen as a wing- threequarter. He equalled E.T. Gurdon’s record of fourteen England caps and would have received many more if the Rugby Football Union had not clashed with the International Board and refused to play in Four Nations matches in 1888 and 1889.

In an age in which tries were not common and matches were low-scoring affairs, he scored five tries and kicked seven conversions in an England shirt. In 1894 he captained England to one of their greatest victories when they routed Wales using the Principality’s own four three-quarter system for the first time.

Lockwood was unquestionably the most outstanding English back of his day - only Welsh captain and rival centre Arthur Gould could compare. Yet he has been forgotten. The official centenary history of the Rugby Football Union (RFU) doesn’t even mention him while O.L. Owen’s earlier book on the RFU notes him only in passing and doesn’t refer to his captaincy of England.

The World’s Wonder

Richard Evison Lockwood was born on 11 November 1867 to a labouring family in Crigglestone, near Wakefield.

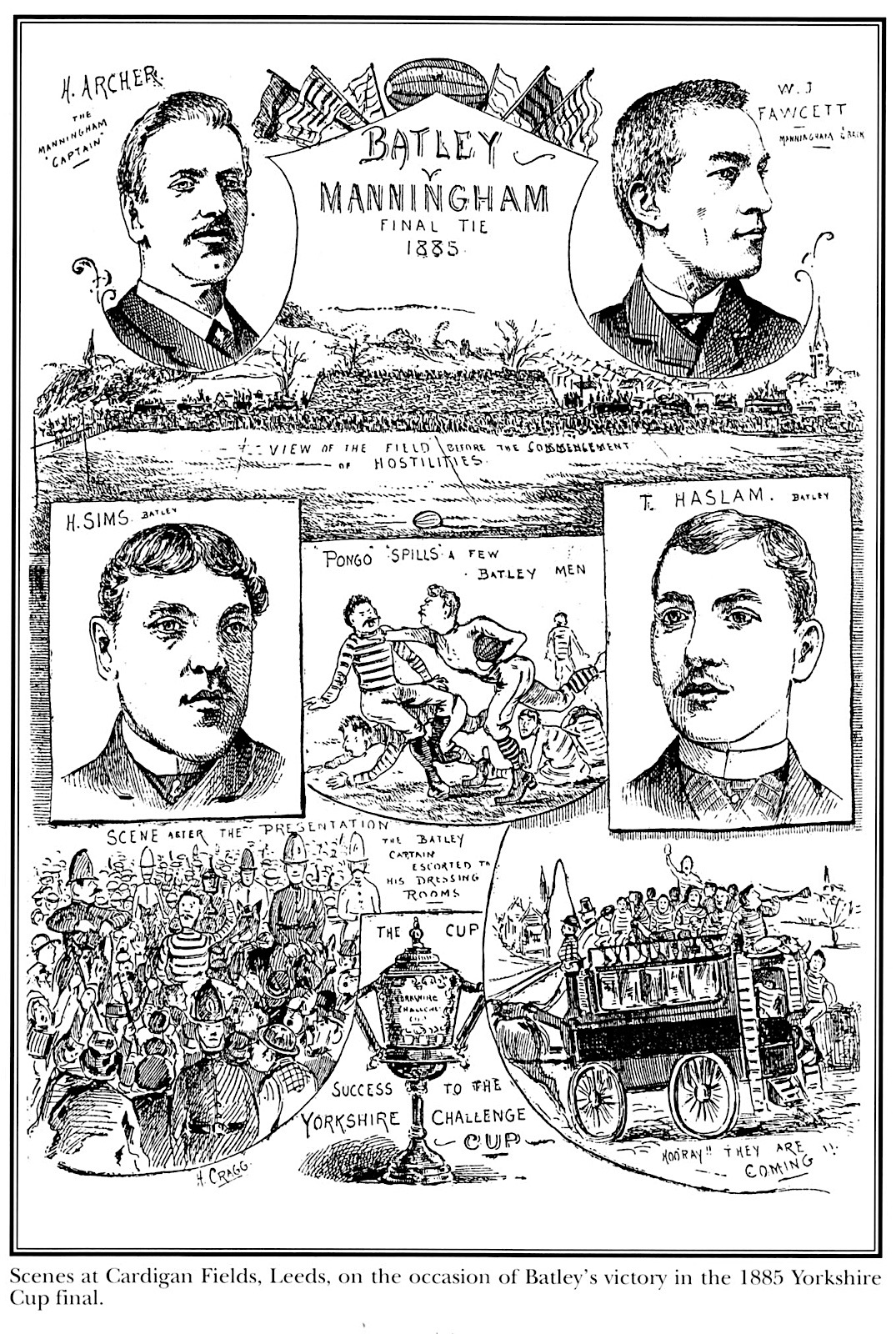

His rugby career began at the age of sixteen for Dewsbury - then one of the North’s leading sides - when he made his debut on the right wing against Ossett in November 1884, a few days before his seventeenth birthday. In those days most English sides played with just three three-quarters but Dicky could play on the wing or in the centres with equal accomplishment.

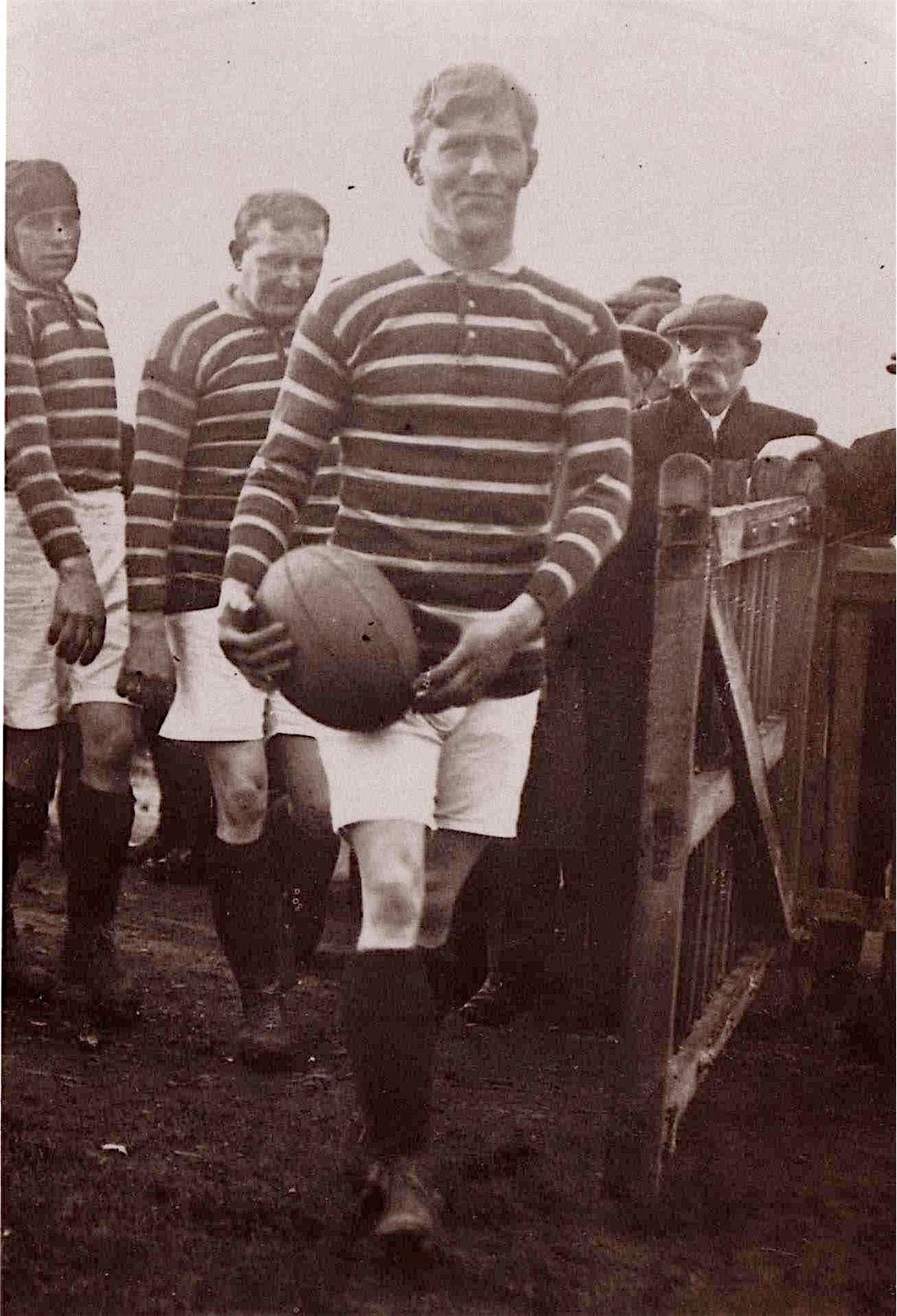

He quickly became a phenomenon and was nicknamed ‘the Little Tyke’ and ‘Little Dick, the World’s Wonder’, partly because of his youth and also because of his diminutive stature - he was only five feet, four and a half inches tall. Even at an early age he was the complete footballer, brilliant in attack, deadly in the tackle and precise in his kicking, with a knack of being in the right place at the right time.

In 1886 he was selected for the first of his forty-six appearances for the Yorkshire county side and shortly after his nineteenth birthday he played for the North against the South, an annual match that was a trial for England selection.

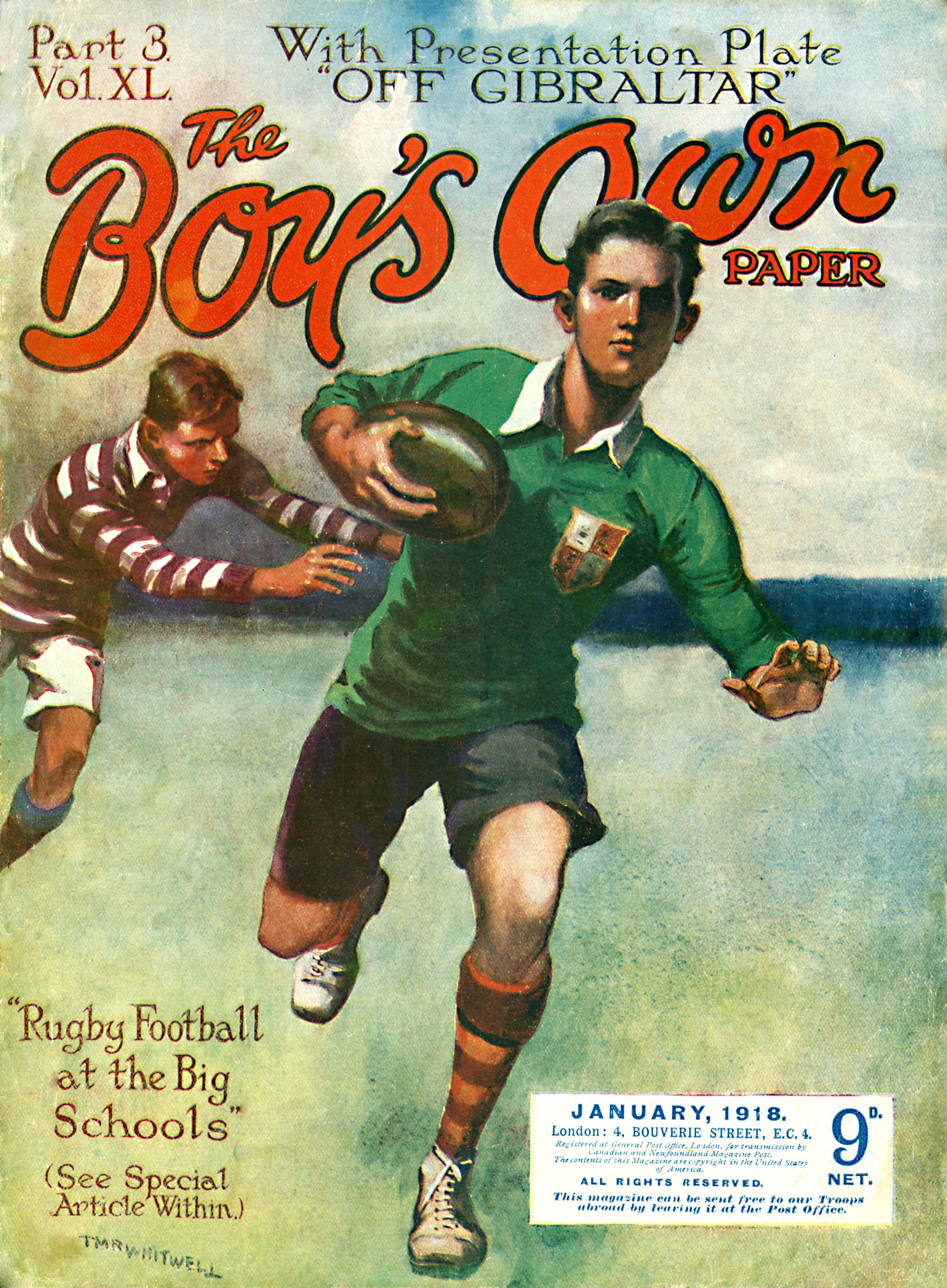

Even at this stage his fame was such that crowds gathered in Dewsbury market place to hear telegram reports from the match being read out. The following month, in January 1887, he made his England debut versus Wales at Llanelli. Dicky-mania quickly engulfed the Dewsbury area, demonstrating that sporting stardom and fan hysteria were not born in the 1960s.

Leaving Dewsbury’s Crown Flatt ground after a blinding display in a Yorkshire Cup tie against Wakefield Trinity, the weekly magazine The Yorkshireman reported that Lockwood ‘was mobbed by a vast crowd which, contracting as the road narrowed, actually pushed down a strong stone wall and then shoved a hawker and a little lad through the aperture into the field below’.

Pictures of Dicky were sold outside of the ground and by photographers’ shops in Dewsbury itself, one enterprising trader charging one shilling and a penny per photo, almost one-eighth of the nine shillings weekly wage the player himself then received as a woollen printer in Walmsley’s local textile mill. Playing in Dublin against Ireland in February 1887 he was carried off with a broken collar bone, filling Dewsbury with wild rumours that he had actually been killed in the match. Hundreds waited through the night at Dewsbury railway station to see him come home from the game, just to prove to themselves that their ‘Little Wonder’ was still alive.

On Trial

In 1889 Dicky shocked his fans and left Dewsbury to play for Heckmondwike, a mill town a few miles down the road, which, thanks to an aggressive policy of attracting players through match payments and jobs, boasted one of the best teams in the county, which included England players such as the forward Donald Jowett and three-quarter John Sutcliffe, one of the few men to be capped by England at both soccer and rugby.

Although his ostensible reason for moving was to play for a better team, it was widely reported that he had told friends that ‘he had got all he could out of Dewsbury and that he was going to Heckmondwike to see what he could get there’. Contrary to RFU’s strict amateur regulations, he allegedly received one pound per match to play for the club and was given the tenancy of The Queen’s Hotel pub in Heckmondwike.

Such blatant flouting of the amateur regulations was too much for the Yorkshire rugby union, who were in the middle of attempting to exorcise the professional devil from their midst. Dicky was investigated by the Yorkshire Rugby Union (YRU) about his transfer to see if any money had changed hands or promises of work been made. Being unable to find any direct evidence, the YRU found him not guilty of the charge of being a professional.

That night in Heckmondwike, the Yorkshireman reported that ‘hundreds of people collected in the market place and its approaches, and the news of his acquittal was received with an outburst of cheering, the gathering in all respects resembling those witnessed at an exciting political election.’

But in December he was again summoned to appear before the YRU committee, where he was charged once more with professionalism and cross-examined by the Reverend Frank Marshall, headmaster of Almondbury school and leading YRU official. Marshall claimed that Morley tried to induce Dicky to transfer to them in 1886 with an offer of an apprenticeship but that Dewsbury kept him by offering 10s a week and £1 per exhibition match.

The ‘trial’ lasted for three days and Dicky showed an admirable talent for stonewalling, as the follow extracts from the cross-examination shows:

Marshall: ‘What year were you asked to go to Morley?’

Lockwood: ‘1886 about.’

Marshall: ‘What was the inducement?’ Lockwood: ‘Nothing.’

Marshall: ‘Do you know Mr Crabtree of Morley?’

Lockwood: ‘Yes.’

Marshall: ‘What did he offer you?’ Lockwood: ‘He did not offer to apprentice me to him. I was not paid anything. If anyone stated I was paid it would be wrong.’ Marshall: ‘A gentleman has stated that you were paid 10s a week.’

Lockwood: ‘Well, that gentleman is wrong.’ ... Marshall: ‘I want you to be very particular about this. I have positive information that you were paid after refusing to go to Morley.’ Lockwood: ‘I was not, sir.’

Marshall: ‘I understand you were paid £1 for exhibition matches.’

Lockwood: ‘That is wrong.’

Marshall: ‘Were you in a position to go to these matches and lose your wages?’

Lockwood: ‘Then I was, sir.’ ...

Marshall: ‘I want to be explicit on this point, as to the meaning of ‘dinners’. Have you ever been told that, seeing that you were not so well off, you could have ‘dinners’ if you went to play with any club?’

Lockwood: ‘No, never.’

Unable to penetrate Dicky’s defence, the YRU committee simply gave up and acquitted him yet again.

Nevertheless, controversy still dogged his career. Unlike his nearest equivalent of the time as a regional sporting hero, Arthur Gould, Dicky was unambiguously working class, a serious handicap to gaining the respect of those who ran the game: ‘Dicky doesn’t sport sufficient collar and cuff for the somewhat fastidious members of the committee,’ the rugby writer of The Yorkshireman reported in 1891.

The tension between Dicky and the game’s authorities epitomised the relationship between the supporters of amateurism who ran the game and working class players who had come to dominate its playing. In 1891 he was passed over for the Yorkshire county captaincy in favour of Oxford-educated William Bromet. ‘It is simply a case of pandering to social position, nothing more nor less. We thought we were ‘all fellows at football’; yet an alleged democratic Yorkshire committee can still show a sneaking fondness for persons who are... we had almost said in a better social position than ourselves’ complained the same correspondent.

Captain of England

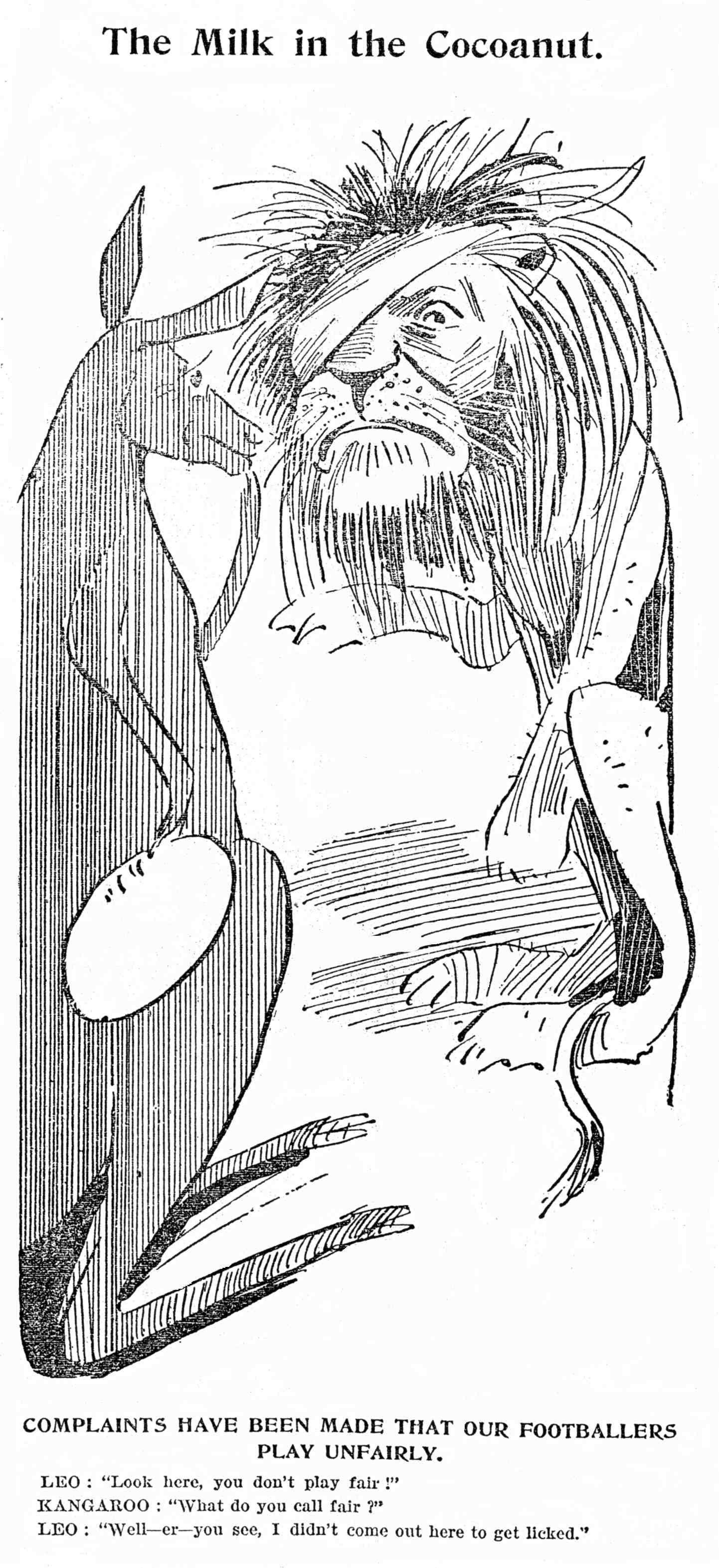

Eventually talent did prevail and in 1892 Dicky was chosen as the captain of the Yorkshire county side, leading them to a hat-trick of county championships over the next three years. His captaincy was notable for more than just his continuation of Yorkshire dominance of the county championship. He helped to implement the Welsh system of playing with four three-quarters. Previously the dominance of northern forwards meant that clubs were reluctant to move to the four three-quarter system first used by the Welsh national side in 1886. ‘Buller’ Stadden had unsuccessfully introduced the system to Dewsbury when he moved there from Cardiff in 1886, but Oldham were the first northern side to use it regularly when Bill McCutcheon joined them in 1888 from Swansea.

Even then, there was still widespread doubt in Lancashire and Yorkshire as to its usefulness - despite northern admiration for the back play of Welsh clubs like Newport, it was believed that its success in Wales was due to the poorer quality of Welsh forward play, especially in comparison to club football in the north of England. When it came to be widely, although not universally, accepted in England in the early 1890s, it was partly due to Lockwood’s influence and the success of the Yorkshire side in using the new system.

Dicky’s unique combination of all-round skill and tactical innovation reached their highest point in 1894, when he was chosen to captain England against Wales at Birkenhead. Playing with four three-quarters for the first time, the English side routed Wales at their own game, winning by 24 points to 3, the highest score by England since the very first Anglo-Welsh game in 1881.

It was, said the Liverpool Mercury, ‘not a beating, it was an annihilation’. Dicky himself scored a try and kicked three conversions, totally outplaying his opposite number Arthur Gould. The most potent factor in this historic victory, according to the Yorkshire Post, ‘was Lockwood, who covered Gould with merciless persistency, and in all his long career Lockwood has never played with greater judgement or effect’.

Even more significant than the victory was Lockwood’s personal achievement in becoming captain of England. Rugby was led on and off the field by middle class ex-public school boys, yet here was an unskilled manual labourer with little secondary education leading men who were, according to all of society’s norms at the time, several times his social superior. It was almost as if a conscript private had taken charge of an elite cavalry regiment. His captaincy symbolised the rise of the working class player in rugby, something which many in rugby’s hierarchy had steadfastly vowed to oppose.

The month after the defeat of Wales, he captained the national side against Ireland at Blackheath, only to go down to defeat by 7 points to 5. Badly hampered by a lack of possession, Dicky scored England’s only try of the match by charging down a kick from the Irish full-back Sparrow, a try acclaimed as: ‘one of the finest pieces of work in the direction of taking advantage of an opponent’s weakness ever seen in first-class football’. Although no-one knew at the time, this was to be not only his last appearance as England captain, but also his last appearance in any type of representative football.

Shortly after the Ireland match he informed the English selectors that he would not be available for the Calcutta Cup match in Edinburgh because he couldn’t afford to take time off work to travel up to Scotland and back. Despite this, he asked the RFU for permission to play for Heckmondwike in a home game taking place on the same day. The Rugby Union refused point-blank to allow him to play for his club - despite the fact Eton house master Cyril Wells had been allowed in similar circumstances to play for Harlequins after pulling out of the Rest of England team beaten by Yorkshire the previous season.

This caused a considerable furore in Yorkshire, where it was seen as gross hypocrisy on the part of the RFU and one more example of how working class players were treated differently from those with a public school background.

The affair added yet more impetus to the calls for working class players to be paid broken time money to compensate for time lost at work due to playing rugby. Disgusted with the RFU and by the Yorkshire Rugby Union’s failure to support him fully, Lockwood announced his retirement from representative football for both England and Yorkshire. Years later, he hinted that he thought he may have been the victim of a conspiracy, commenting that ‘there was always a strong feeling against us’ on the part of the RFU leadership.

1895 And After

Dicky therefore came to embody the growing crisis that was engulfing English rugby union an which led in August 1895 to English rugby splitting in two and the formation of the Northern Union.

Unsurprisingly, given his treatment at the hands of the leadership of rugby union, Dicky was quick to show his support for the new body. He quickly left Heckmondwike, who remained temporarily loyal to the RFU, to join Wakefield Trinity as their captain. He made one appearance for the Yorkshire county Northern Union representative side in 1897 but his rugby league career was beset by age and severe personal problems.

In January 1897 he was declared bankrupt after accumulating debts of over £300 running his pub and was forced to sell all of his household furniture to pay off his creditors. Even so, his own difficulties did not stop him helping to organise charity fund-raising matches for the trade unions during the engineers’ lock out during the same year.

In November 1900, the wheel turned full circle and ‘Little Dick, the World’s Wonder’ returned to Dewsbury to play out the final three years of his career. Over a hundred years later, viewers of the Mitchell & Kenyon collection of Edwardian Northern Union rugby films were able to see footage of him run on to field at Crown Flatt as Dewsbury prepared to take on Manningham in October 1901. Following retirement as a player he spent the rest of his years in manual jobs until on 10 November 1915, just a day before his 48th birthday, he died in Leeds Infirmary. His death occurred shortly before he was due to have a second operation for cancer, and he left a widow and four children. He was buried in Wakefield Cemetery.

Although forgotten in rugby union history, Dicky’s memory flickered on in rugby league, which was the continuator of the glory years of pre-1895 Yorkshire and Lancashire rugby union. Thirty-five years after Lockwood’s retirement, one rugby league writer recalled ‘Dicky Lockwood’s Deadly Tackle - once felt, never forgotten’, while over a century after his birth, Eddie Waring was to regret the fact that he could not include him in The Great Ones.

The virtual disappearance of Dicky Lockwood’s name from the annals of English rugby serves as a warning that sportsmen and women are not simply remembered for their achievements on the field of play. Their survival in the folk memory of sport is dependent on the role they can play in the creation of a mythic past. Thus Arthur Gould’s name lives on in Welsh rugby union because he seemed to embody the spirit of the emerging Welsh national identity of the turn of the century. Likewise, Adrian Stoop was the personification of the dashing Edwardian English public school hero and the idealisation of everything the RFU stood for. Dicky, in contrast, could play no such role.

Indeed, to the supporters of the RFU he represented everything they wanted to forget: the virtual eclipse of middle class players by Northern manual workers in the 1890s, the rise of professionalism and the near loss of control of a sport they viewed as being uniquely theirs. Even the fact that he was a fleet-footed three-quarter seemed an affront to official rugby union history - insofar as it was spoken about at all, the Northern game before the split was thought to be so dominant because of its hardworking forwards, horny- handed sons of toil who were happy to carry out the donkey work while public school-educated backs used superior intelligence to fashion brilliant tries.

It is high time that Dicky Lockwood was restored to his rightful position as one of the greatest English players of either rugby game.

His achievements rank among the most outstanding of any age. Yet his excision from history also serves to remind us that sport is no less subject to political and social prejudice than any other form of human activity. For those who assume that sport stands above society and that excellence inevitably brings it own rewards, the career of Richard Evison Lockwood is powerful evidence to the contrary.

-- This is a slightly edited version of a chapter from my 2009 book 1895 And All That.