I'm publishing the article below in tribute to David Storey, who died today. It originally appeared under the title 'Sex, class and the critique of sport in This Sporting Life' as a chapter in the 2013 book 'Fields of Vision: The Arts in Sport' edited by Doug Sandle, Jonathan Long, Jim Parry and Karl Spracklen.

Lindsay Anderson’s acclaimed film version of David Storey’s 1960 novel This Sporting Life (for which Storey also wrote the screenplay) was released in 1963. Born into a mining family in Wakefield in 1933, Storey had won a scholarship to the local Queen Elizabeth Grammar School. After leaving, he somewhat incongruously straddled his new and old worlds by studying at London’s Slade School of Fine Art while playing rugby league for Leeds ‘A’ (reserve) team at the weekends. At the age of eighteen he had signed a contract for Leeds because, he later recounted, “what I really wanted to do was go to art school. Taking the contract was going to be the only way I could pay for my education”(Observer Sports Monthly, 2005: p. 7). It was from that experience from which the novel was drawn.

Storey’s life was that of a classic working-class grammar school boy, caught between the two contrasting and often conflicting worlds of his past and his future. This was something of which he was acutely aware during his time as a a rugby league player: “being perceived as an effete art student often made the dressing room a very uncomfortable place for me”(Observer Sports Monthly, 2005: p. 7). Nor was his time at art school happy: “at the Slade meanwhile I was seen as a bit of an oaf,” he later remembered (Campbell, 2004: p. 31). His description of the character Radcliffe in his eponymous 1963 novel - “Grammar school broke him in two” - seems to have applied equally to himself. Storey’s ambiguity towards rugby league and sense of alienation from his surroundings inform the narrative of both the novel and the film.

The heart of the novel describes the relationship between the rugby league player Arthur Machin and his widowed landlady Valerie Hammond (their names were changed to Frank and Margaret in the film), combining a finely wrought understanding of the emotional entanglement of the couple with an accurate, if one-sided, description of the seamier realities of rugby league. As in the novel, the film depicts Machin as a young man largely impervious to the world around him, while Mrs Hammond is a woman crushed by the society around her. Although the plot is compressed in the screenplay, the film parallels the major events and the characterisations of the novel as if on tramlines, but Lindsay Anderson’s direction allows the nuances and complexities of the relationships between the major characters to be drawn out visually, arguably giving the film a greater emotional subtlety than is achieved by the novel.

Both the novel and the film are firmly located in what became known in the late 1950s as the ‘kitchen sink’ drama that aimed, largely for the first time in mainstream British culture, to portray the lives of working-class people in a realistic and usually sympathetic framework. The most prominent examples of the genre were Alan Sillitoe’s novels and their film versions Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960) and The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962) and Shelagh Delaney’s play and subsequent film A Taste of Honey (1961). But This Sporting Life differs fundamentally from Sillitoe’s work (and Delaney’s in a different sense). Although many have described Frank Machin as a ‘working-class hero’ or anti-hero in the mould of Sillitoe’s Arthur Seaton (Saturday Night and Sunday Morning) or Colin Smith (The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner) this is not strictly accurate. Sillitoe’s characters are conscious rebels, kicking against a society which seeks to force them into roles they are not prepared to accept. ‘Don’t let the bastards grind you down,’ Seaton memorably proclaims at the start of Saturday Night and Sunday Morning.

Lindsay Anderson and Richard Harris at Wakefield Trinity's Belle Vue ground.

In contrast, Frank Machin is not a rebel. His desire to conform and be accepted is hampered only by his inability to understand the codes by which he is expected to live his life, not by his rejection of them. This difference was recognised by Anderson, who told Sight and Sound during the shooting of the film that “Saturday Night and Sunday Morning was a thoroughly objective film, while This Sporting Life is almost entirely subjective… I have tried to abstract the film as much as possible from so as not to over-emphasise the locations and keep attention on the situation between the characters” (Milne, 1962: p. 115). Indeed, in contrast to Sillitoe’s work, This Sporting Life has more in common with Walter Greenwood’s pre-war novel Love on the Dole, with its depiction of stultifying conformity and the extinguished hopes of working-class people.

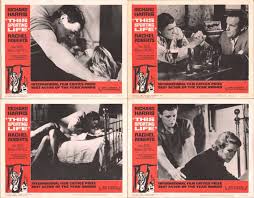

Produced at the end of the New Wave of British realist cinema, the film of This Sporting Life was a major success in Britain and America, with Harris being nominated for an Oscar. Filmed in stark black and white and unremittingly bleak in tone, it was shot largely in Leeds and at rugby league grounds at Wakefield Trinity (for the match scenes) and Halifax (for the external, post-match shots). Somewhat incongruously, a library shot of a crowd at a Twickenham international match can also be fleetingly glimpsed after Machin is seen scoring a try. Anderson made full use of Wakefield Trinity’s players and coaching staff (indeed, the first lines of the film are spoken by former Great Britain player and then Trinity coach Ken Traill), and one of the most memorable scenes is of a flowing movement leading to a try mid-way through the film, which is actually footage of Wakefield’s try in their 5-2 defeat of Wigan in the quarter-final of the 1963 Rugby League Challenge Cup.

Although the film was welcomed by many people in rugby league for putting the sport in the public eye - Harris was made an honorary president of Wakefield Trinity and its players and officials were invited to the premiere - it was not welcomed by everyone in the sport. At a discussion at the 1963 annual meeting of the Yorkshire Federation of Rugby League Supporters’ Clubs, representatives of Hull Kingston Rovers complained that the film was not a fair reflection and was ‘detrimental to the rugby league code’. Supporters from Wakefield Trinity claimed that they were not aware of ‘the true nature’ of the film until it was premiered, presumably not having bothered to read the book (YFRLSC minutes, 15 June 1963). Reviewing the film for the Rugby Leaguer, the sport’s weekly newspaper, Ramon Joyce (a pseudonym used by Raymond Fletcher, who later became the Yorkshire Post’s chief rugby league correspondent) commented that ‘my worst fears of the film… were unfortunately realised’ (Joyce, 1963: p. 4). This attitude towards the film has persisted in rugby league circles, to the extent that the editor of one of the sport’s weekly newspapers told the author in 2012 that he felt that the film was ‘anti-rugby league’.

Transgressive relationships

However, such a narrow view is akin to not seeing the wood for the trees. Despite appearances, this is not actually a film about rugby league or sport, it is a film about relationships and the stifling conformity that crushes the human spirit and distorts sexuality. Rugby league is, as it was and remains in industrial West Yorkshire and other parts of the north of England, part of the complex social structure that provides the context and the backdrop for the personal drama that unfolds. The sport’s acute sense of class position and its rootedness in the region’s industrial working-class culture allowed both Storey and Anderson to highlight the underlying personal tensions of working-class life with a directness that would be impossible using either soccer, where full-time professionalism distanced players from the local community, or rugby union, which was animated by an explicitly middle-class value system.

Indeed, one might mischievously suggest that if Tennessee Williams had been born in Castleford, Yorkshire rather than Columbus, Mississippi, This Sporting Life is perhaps the type of screenplay he would have written. Subtle class distinctions, suffocating social norms and transgressive and dysfunctional sexual relationships are as central to This Sporting Life as they to Williams’ plays. And, of course, Richard Harris’s somewhat uneven performance in the film - most notably in his inability to master the local accent - is rather obviously derived from Marlon Brando’s portrayal of Stanley Kowalski in Elia Kazan’s 1951 film version of A Streetcar Named Desire.

As with Williams’ work, sex is central to This Sporting Life. In the opening scene, after Machin has his teeth broken by a stiff-arm tackle that leaves him unconscious, the first thing that Ken Traill, the real-life rugby league international who portrayed the fictional team coach in the film, says to him is that ‘you won’t want to see any tarts [women] for a week’.

Before he signs for the club, Machin’s first encounter with the rugby league team is at a dance hall in the city centre when he cuts in on a dance between a player, Len Miller, one of the rugby’s club ‘hard men’. and a young woman. Miller tells him to go away and when Machin refuses, Miller says to him, ‘Do you want a thumping, love?’ and they then go outside to fight. The use of the word ‘love’ between two men, although commonly in usage by miners and other men in the Yorkshire coalfields until at least the 1980s, would have appeared to most viewers of the film to be at odds with the aggressively heterosexual world portrayed on the screen.

Most importantly, almost all of the relationships in the film do not fall within the bounds of what would be assumed to normative sexual relations in the north of England in the late 1950s/early 1960s.

The principal relationship in the film is that between Machin and Margaret Hammond, the widow with whom he lodges. Mrs Hammond’s husband has been killed in an industrial accident in the engineering factory owned by the rugby league club’s chairman, Gerald Weaver, leaving her with two small children. The direct cause of his death is unclear, although Weaver later tells Machin, perhaps maliciously, that it is believed that he committed suicide to escape his wife. The relationship between Machin and Mrs Hammond is frosty, fraught and almost entirely uncomfortable, even when he falls in love with her, and eventually results in him violently raping her. As Lindsay Anderson later described it, this is an ‘impossible story of a fatally mismatched couple’ (Anderson, 1986)

Although this is not highlighted in the film as prominently as it is in the novel, Mrs Hammond (she is almost never referred to by her first name) is clearly significantly older than Frank, who would appear to be in his early twenties. Her life experience, much of it tragic, is clearly something that the much younger Frank does not understand and the cause of much of his frustration and subsequent violence towards her. Their age difference is something that clearly falls outside of what is deemed to be a ‘respectable’ relationship, as can be seen by the reactions of Mrs Hammond’s neighbours to Frank, most notably when he returns home with the gift of a fur coat for her, much to the silent disgust of her visiting next-door neighbour.

Machin’s other major relationship is with, ‘Dad’ Johnson, played by William Hartnell, the club scout who arranged for him to have a trail for the team which led to him signing a contract to become a professional player. The suspicion that Johnson’s interest in Frank has a strong homo-erotic element is articulated by Mrs Hammond: ‘he ogles you. He looks at you like a girl’, she complains to Frank, who, from his reaction, is also aware of Johnson’s attraction to him. Perhaps as a consequence of this knowledge, Machin is needlessly cruel to Johnson on several occasions, taking advantage of the older man’s feelings. Johnson’s effeminacy is emphasised by Mrs Hammond again, who complains that he has soft hands, by club chairman Gerald Weaver, who calls him Frank’s ‘little dog’ and also in a scene when the players get off the team coach and pass a ball amongst themselves. It is passed to Johnson, who drops it - a sure sign of effeminacy in the intensely competitive male world of sporting prowess.

Alan Badel as Mr Weaver

Gerald Weaver himself also seems to have interests in Frank above mere rugby. Gloriously played by Alan Badel, he seems to flirt with Frank, the sexual undertone mixing with the fact that, now that Frank has signed for Weaver’s team, he is Weaver’s property. Giving Frank a lift home in his car, Weaver ostentatiously puts his hand on Frank’s knee, an act that Frank clearly suspects is something rather more than mere friendliness. However, as with Miller’s use of the word ‘love’ to Machin in the earlier dance hall scene, it should be noted that this type of close physical contact, such as squeezing another man’s knee, between men of the industrial working class was, and continues to be, common in the north of England. The ambiguity of a middle-class man like Weaver making physical contact with a working-class man such as Machin raises questions not just of sexual but also class transgression.

On a personal level, Machin’s consciousness of the sexual undertone in his relationships with Weaver and Johnson may also reflect something about himself. The pin-ups in his room at Mrs Hammond’s house are all of male boxers or rugby players and the film pays particular attention to the fun Frank has in the communal plunge bath that all the players use after a match.

The fourth overtly transgressive relationship is that involving Mrs Weaver (played by Vanda Godsell), the wife of Gerald Weaver, who invites Machin to her home when her husband is at work. Like Mrs Hammond, she too is considerably older than Frank but unlike Mrs Hammond, she is sexually confident and attempts to seduce him. She fails because Frank tells her that he thinks it is unfair on Mr Weaver, an excuse that Mrs Weaver finds puzzling, suggesting that she and her husband have a non-monogamous marriage. She suspects Frank’s reticence is because he is in love with Mrs Hammond. ‘Is it the woman you live with?’ she snaps at him, to which he quickly corrects her: ‘she’s the woman I lodge with’ he says, emphasising the gulf of respectability that separates the two words.

Moreover, Frank is clearly not the first player that Mrs Weaver has invited back home. Team captain Maurice Braithwaite disparagingly calls her ‘Cleopatra’ and Arthur Lowe, playing Weaver’s rival director Charles Slomer, asks Frank about ‘what I call Mrs. Weaver's weakness for social informalities’. Moreover, the Weavers’ Christmas party that the team attends appears to resemble an orgy, something alluded to in the promotional posters for the film, which emphasised the sexual aspects of the film over its sporting ones.

In fact, all of Machin’s principal relationships in the film could be termed as sexually transgressive or potentially so, concerning either homo-erotic attraction or cross-generational heterosexual relationships. The only ‘normative’ relationship in the film is that of Maurice Braithwaite (played by Colin Blakely) and his fiance Judith (played by Anne Cunningham), whose blossoming courtship runs through the narrative, culminating in their marriage at the end of the film, presenting an oasis of respectable conformity in contrast to the complexities and frustrations of Frank’s tortured emotional life.

Conclusions

There are two key points to be made about the sexual politics of the film. The first one is that This Sporting Life presents the complexity of relationships within a working-class community in a way that had never previously happened in British film, and this in itself is an important achievement. Of course, some of the same themes can be seen in other British new wave films. For example, the figure of the older woman appears in Room at the Top and Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (in which she is also played by Rachel Roberts) and homosexuality is dealt with in A Taste of Honey. However, This Sporting Life is unique in the range and complexity of the sexual relationships, both overt and implied, it portrays not only in a working-class community but also across classes.

The second point is perhaps more intellectually interesting. What is the relationship between the portrayal of sport in the film and the centrality of sex to its plot?

Lindsay Anderson and David Storey, whether consciously or not, set up the film’s shifting sexual scenario against the norms of sport. Anderson, the public-school educated gay intellectual is the outsider looking in and Storey, the working-class, rugby league-playing grammar school boy, is the insider looking out. Together, they instinctively grasped that the nature of sport is based on the reinforcement of traditional heterosexual masculinity. Sport is a masculine, aggressively heterosexual world, in which might is right and weakness punished. This is a world that Frank Machin understands. But his mastery of that world puts him at a disadvantage in the real and complicated world of sex and personal relationships. And this tension between sport and sex, I would argue, is the driving force of the film.

Although it can be argued that This Sporting Life presents an unfairly brutal and bleak portrait of rugby league - for example, no player expresses any enjoyment in playing the game - the film should be seen solely as a critique of rugby league, but of sport as a whole. Modern sport is founded on a rigid differentiation between men and women, the masculine and the feminine, the sexually normative and the transgressive. This was summed up in the Muscular Christian motto ‘Mens sana in corpore sana’ - ‘a healthy mind in a healthy body’, which referred to not the creation of intellectual minds in healthy bodies, but of morally pure minds, free of the temptations of sexuality (Haley, 1990).

Tom Brown’s Schooldays, modern sport’s foundational text in which rugby and cricket were raised to the level of moral education, served as a handbook for this Muscular Christian worldview. The book explains that new boys who did not ‘fit in’ with their schoolmates would sometimes get “called Molly, or Jenny, or some derogatory feminine name” (Hughes, 1989: p. 218). In the second part of the book Tom Brown and his best friend East are approached by “one of the miserable little pretty white-handed curly-headed boys, petted and pampered by some of the big fellows, who wrote their verses for them, taught them to drink and use bad language, and did all they could to spoil them for everything in this world and the next” (Hughes, 1989: p. 233). Unprovoked, they trip him and kick him, much like Machin’s treatment of ‘Dad’ Johnson. This campaign against effeminacy and homosexuality also animated the drive to place sport at the heart of the school curriculum as a way of diverting male adolescent energies that might otherwise have taken a sexual direction (Puccio, 1995: p. 63).

The link between sport and opposition to transgressive sexual practices was highlighted by the activities of some the nineteenth century’s leading sporting figures of the time. Lord Kinnaird, president of the FA for thirty-three years, was a prominent supporter of the Central Vigilance Society for the Suppression of Immorality and the National Vigilance Society, which in 1889 was behind the jailing of an English publisher for publishing 'obscene' works by Zola and Flaubert (Sanders, 2009: p. 77). Edward Lyttleton, captain of the Cambridge University cricket team and a batsman with Middlesex, campaigned against the alleged dangers of masturbation. And of course it was the Marquess of Queensberry, one of the founders of the Amateur Athletic Association and the man after whom the laws of modern boxing are named, who was fatefully sued by Wilde in 1895 for calling him in ‘Somdomite [sic]’ (Hall and Porter, 1995: p. 144). Modern sport was founded on the most rigid imposition of conformity, social and sexual.

In contrast to this Manichean world, This Sporting Life presents the richness and complexity of sexual desire as it struggles against the oppressive conformity of gender roles and class distinction. It portrays sport as the accomplice and the instrument of sexual oppression and misery. In this way therefore, This Sporting Life could be said to be the Anti-Tom Brown’s Schooldays.

It has long been argued that sport is rarely successful in films. This Sporting Life is successful however - but that is because it is not really about sport, or rugby league, at all.

It is all about sex.

Bibliography

Campbell, James (2004) ‘A Chekhov of the North’, Guardian, 31 January, p. 31-32.

Haley, Bruce (1990) The Healthy Body and Victorian Culture, Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Hill, Jeff (2006), ‘Acting Big’: David Storey’s This Sporting Life’ in his Sport and the Literary Imagination : Essays in History, Literature, and Sport, Oxford: Peter Lang.

Hill, Jeff (2004), ‘Sport Stripped Bare: Deconstructing Working-Class Masculinity in This Sporting Life’, Men and Masculinities, Vol. 10 No. 10: pp. 1-19.

Holt, Richard (1996) 'Men and Rugby in the North', Northern Review, Vol: 4: pp. 115-123.

Hughes, Thomas (1989) Tom Brown’s Schooldays, Oxford: OUP World’s Classics edition.

Hughson, John (2005) ‘The 'Loneliness' of the Angry Young Sportsman’ Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies Vol. 35, No. 2 pp. 41-48.

Hutchings, William (1987) ‘The Work of Play: Anger and the Expropriated Athletes of Alan Sillitoe and David Storey’, Modern Fiction Studies, Vol. 33, No.1: p. 35.

Joyce, Ramon (1963) Rugby Leaguer, 15 February, p. 4.

Mansfield, Jane (2010) ‘The Brute-Hero: The 1950s and Echoes of the North’, Literature & History, Vol. 19 No. 1: p. 34-39.

Milne, Tom (1962) ‘This Sporting Life’, Sight and Sound, Vol. 31, No. 3: p. 113-116.

Observer Sport Monthly (2005) 'The Fifty Best Sports Books of all Time', 8 May: pp. 5-9.

Pittock, Malcolm (1990) ‘Revaluing the Sixties: "This Sporting Life" Revisited’, Forum for Modern Language Studies, Vol. 26, No. 2: pp. 97-108.

Porter, Roy, and Hall, Lesley (1995) The Facts of Life, Yale: Yale University Press.

Puccio, Paul M. (1995) ‘At the Heart of Tom Brown’s Schooldays: Thomas Arnold and Christian Friendship’, Modern Language Studies, Vol. 25, No. 4: pp. 57–74.

Sanders, Richard (2009) Beastly Fury: The Strange Birth of British Football, London: Transworld.

Shafer, Stephen C. (2001) ‘An Overview of the Working Classes in British Feature Film from the 1960s to the 1980s: From Class Consciousness to Marginalization’, International Labor and Working-Class History, Vol. 59: pp. 3-14.

Solomon, R. H. (1994) ‘Man as Working Animal: Work, Class and Identity in the Plays of David Storey’, Forum for Modern Language Studies, Vol. 30, No.3: p. 193.

Spracklen, Karl (1996) ‘Playing the Ball: Constructing Community and Masculine Identity in Rugby: An analysis of the two codes of league and union and the people involved’, unpublished PhD thesis, Leeds Metropolitan University.

Storey, David (1998) Radcliffe, London, Vintage.

Storey, David (1962) This Sporting Life, London: Penguin.

Yorkshire Federation of RL Supporters’ Clubs [YFRLSC] (1963) annual conference minutes, 15 June.