If we look at the context in which football developed in Victoria in the mid-nineteenth century, we find that there is nothing uniquely Australian about the rules of football played in the colony at that time. As Hobsbawm noted, sport was ‘one of the most significant of the new social practices’ of this period for the middle classes as much as the working classes, because ‘it provided a mechanism for bringing together persons of an equivalent social status otherwise lacking organic social or economic links’.(2)

Wills, Thompson and the rest of the Melbourne football pioneers were merely emulating the activities of their equivalents in Britain. ‘Football’ in its generic sense was at this time a cultural expression of British middle-class nationalism. ‘It is the very element of danger in our own out-of-doors sports that calls into action that noble British pluck which led to victory at Agincourt, stormed Quebec and blotted out the first Napoleon at Waterloo,’ wrote one Australian commentator, echoing a widespread belief succinctly expressed by the Yorkshire Post that football was one of ‘those important elements which have done so much to make the Anglo-Saxon race the best soldiers, sailors and colonists in the world’.(3)

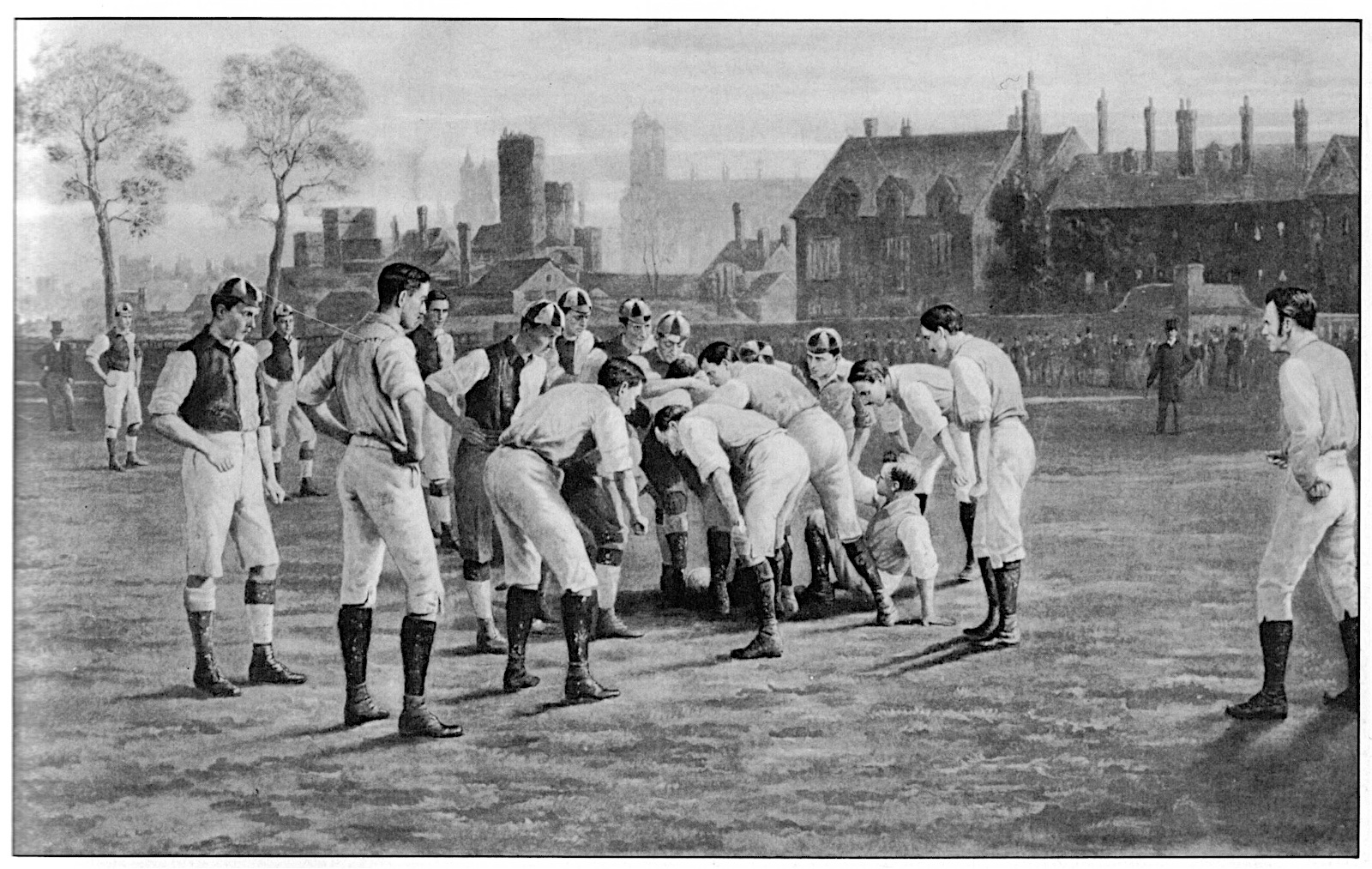

In the mid-nineteenth century, all organised or codified forms of football saw themselves as part of this Muscular Christian cult of games. Football was played not merely for recreational enjoyment, but also for a moral purpose. The sport, whatever its rules, was played for the lessons it taught and the examples it set. It was part of the socialisation of young men and boys across the British Empire, and the wider English-speaking world. Muscular Christianity, and the football which based itself on its principles, was an expression of British cultural nationalism. And the colonies of Australia were nothing if not British. Indeed, as the economist and noted Australian Rules historian Lionel Frost has noted, such was the integration of the Australian colonies with the economy and culture of the British Isles that ‘nineteenth century Australia may therefore be thought of as a “suburb of Britain”.’(4)

So it should therefore not be surprising that when we examine those features of early Australian Rules football that are held to be uniquely Australian, we can find their equivalents in the wider Imperial world of football.

To modern eyes, perhaps the most distinctive difference is the lack of an offside rule. For Rob Pascoe this is the first of the ‘basic laws of Australian Rules which distinguish it from Rugby and reflect Melbourne’s different social history’.(5) Attacking players can advance beyond the ball-carrier, and indeed their opponents, at will and without restriction. In contrast, the rugby codes allow no player to advance beyond the ball carrier and even soccer has an offside rule.

But in the primordial soup of football’s early evolution in the 1850s and 1860s, offside rules were fluid and changing. Although the major public school codes of football had rules regulating off-side play, the original rules of the Sheffield Football Club, formed in 1857 (two years before the first Melbourne rules were drawn up), had no offside rule at all until 1863. Sheffield FC was a considerable factor in the early football in England and by 1867 enough clubs played under its rules for it to form the Sheffield Football Association. (6) It should also be noted that Gaelic football and basketball, although both codified after the Melbourne rules (in 1884 and 1891 respectively), did and do not have offside rules, suggesting the possibility that dissatisfaction with offside restrictions was not uniquely Australia.(7)

Australian Rules’ second distinctive feature is the mark. Robin Grow’s belief that ‘if there is one aspect of the Australian game that distinguishes it from all other codes, it is the mark’ is also shared by almost all historians of the sport.(8) But in fact the mark was commonplace across almost all codes. Commonly known as a ‘fair catch’, the rule allowed a player who caught the ball cleanly before it touched the ground to claim a ‘free kick’, the right to kick the ball unimpeded by his opponents. The second edition of C.W. Alcock’s Football Annual in 1868 outlined in some detail the widespread use of this rule:

Catching the Ball

At Harrow, Rugby, Winchester, Marlborough, Cheltenham, Uppingham, Charterhouse, Westminster, Haileybury, Shrewsbury [public schools], Football Association, Sheffield Association and Brighton [College], catching is allowed, but at Eton, Rossall and Cambridge the ball must not be touched with the hands.

Privileges obtained by a Catch

At Harrow and Shrewsbury, ‘free kick’ with a run of three yards is allowed. According to the Football Association, Sheffield Association, Charterhouse and Westminster, the ball must be kicked at once. Rugby, Westminster, Marlborough, Cheltenham, Haileybury, Brighton and Uppignham allow running with the ball, on certain conditions. At Winchester a player may run with the ball as long as one of the other side follows him: at Uppingham until he is stopped or held. (9)

The original 1863 rules of the Football Association specified that ‘if a player makes a fair catch he shall be entitled to a free kick, provided he claims it by making a mark with his heel at once’. Even the Cambridge version of the sport originally allowed the ball to be handled, as an 1863 description of one of the first games under Cambridge rules highlights: ‘any player may stop the ball by leaping up, or bending down, with his hands or any part of the body’.(10)

Although its use disappeared from the London and Sheffield Football Associations by the late 1860s, the fair catch was already a major feature of the Rugby game. Indeed, the definition of a fair catch was rule number one in Rugby School’s ‘Football Rules’ of 1845.(11) The 1862 rules of Blackheath F.C., a founding member of not only the Rugby Football Union (RFU) but also of the Football Association, in which it defended the use of Rugby rules, defined a fair catch as

a catch direct from the foot or a knock-on from the hand of one of the opposite side; when the catcher may either run with the ball or make his mark by inserting his heel in the ground on the spot where he catches it, in which case he is entitled to a free kick.(12)

This was essentially the definition adopted by the RFU in its ‘Laws of the Game’ at its foundation in 1871, although the complexity of situations affecting the mark meant that its governance stretched across rules twenty-eight, forty-three, forty-forty, fifty and fifty-one. It was not until 1892 that the RFU rules specified that a mark could only be made by a player catching the ball on the ground, thus outlawing what in Australian Rules would be called a high mark, when the mark is awarded to a player who catches a ball while airborne.(13)

The third distinctive feature of the playing of Australian Rules is the fact that the player in possession of the ball can only run with it if it is bounced or touched on the ground regularly (current rules specify that this must be done at least every fifteen metres, although it was originally ‘five or six yards’).(14) Again this can be found in Gaelic football, although given the limited state of scholarly research into the history of that code it is impossible to assess how much the Irish game was influenced by the Australian.

Nevertheless, bouncing the ball to advance it was not unknown in English codes of football in the 1860s. Indeed, the 1864 rules of football as played at Bramham College, a private school in West Yorkshire, explicitly incorporates this rule. Carrying the ball by hand was not permitted but the college’s football rule fourteen stated that ‘the ball may ‘bounced’ with the hand, and so driven through the opposite side’.(15) It is worth noting that this rule was in use at least two years before it was introduced into the Australian game in 1866. [Since this article was written in 2010 it has come to light that the form of football originally played at Princeton University also insisted on running players bouncing the ball and Australian-style hand-passing – see my 2013 article ‘Unexceptional Exceptionalism’]

Some historians, such as Gillian Hibbins, have found a uniquely Australian aspect in Melbourne footballers’ distaste for ‘hacking’ in the Rugby School game and claimed that the Melburnians’ ban on hacking was ‘the chief decision which was ultimately to give rise to a distinctive Australian football game’. Most famously, J. B. Thompson claimed in 1860 that he and his fellow rule-framers forbade hacking because ‘black eyes don’t look so well in Collins Street [Melbourne’s commercial centre]’.

But again, this concern was also widespread in Britain. The FA outlawed hacking and many rugby-playing clubs also forbade hacking, Rochdale, and Preston Grasshoppers being some of the more prominent sides to do so. The reasons were exactly the same as those expressed by J.B. Thompson. Before the first Lancashire versus Yorkshire rugby match in 1870, the Yorkshire captain Howard Wright sought an assurance that his opponents would not hack, because, echoing Thompson, ‘many of his men were in situations and it would be a serious matter for them if they were laid up through hacking, so it was mutually agreed that hacking should be tabooed’.(16)

Alongside the technicalities of playing the game, those who believe that the rules developed in Melbourne were uniquely Australian also point to broader features of the sport. The most sophisticated of these historians is Richard Cashman in his outstanding Sport and the National Imagination. Cashman argues that there are also participatory and spatial issues in Australian Rules that reflect the uniqueness of Australian society in the mid-nineteenth:

Australian football is an expansive game both in terms of the size of the playing field, the number of players - originally there were 25, then 20, then, in modern times, 18 - and the length of play. In the early years play continued until a goal was scored or dusk intervened. ... Some of the large Australian football grounds are approximately twice the size of rugby, soccer or American football grounds. ... The character of Aus fbl reflected this abundance of cheap land in close proximity to cities and suburbs. It is a practical demonstration that Australia has abundant space for sport.(17)

But, again, such features were not unique to Melbourne. Neither the original rules of the FA nor of the RFU specified the number of players in a team. Until 1876, when it was reduced to fifteen, the usual number of players in an adult rugby team was twenty, although school-boy sides would often number far in excess of twenty. At Rugby School, ‘Big-Side’ matches, as described famously in Tom Brown’s Schooldays, regularly had sixty players on each side.(18) Nor was their any fixed period of play specified in the rules of the RFU, the FA or the Sheffield FA. As in Melbourne, teams generally decided that a game was won when one side had scored a specified number of goals. Perhaps the most famous example of this can be found in the 1862 football rules of Rugby School, in which rule thirty-nine stated that: ‘all matches are drawn after five days, or after three days if nogoal has been kicked’.(19)

As Cashman implies, the question of the dimensions of the playing area is one which is regularly highlighted as having a distinctively Australian character. Rob Pascoe in his simultaneously evocative and provocative The Winter Game argues that Australian Rules’ ‘oval and rather carelessly measured’ playing field distinguishes the pre-capitalist mind-set of English football codes from that of Antipodean ‘post-feudal society’.(20)

There are two problems with this assumption. Firstly, as Geoffrey Blainey has made clear, most football grounds in the first fifteen years of the Australian code were not oval but rectangular, exactly the same as every other football code. The first published diagram of player positions, in the Melbourne yearbook The Footballer of 1876, shows a rectangular playing area. Indeed, as late as 1903, the ‘Laws of the Australasian Game of Football’ published by the New South Wales Football League, also showed a rectangular pitch.(21)

The second problem is that the English codes were originally similarly imprecise in their specifications. The Melbourne rules of 1858 and 1860 stated that ‘the game shall be played within a space of not more than 200 yards wide’. The 1866 revised version of the rules were the first to define the length and width of the playing field. Rule one stated that

the distance between the goals shall not be more than 200 yards; and the width of the playing space, to be measured equally on each side of a line drawn through the centre of the goals, not more than 150 yards.(22)

This sounds uncannily similar to the first rules of the FA, whose rule number one stated that ‘the maximum length of the ground shall be 200 yards, the maximum width shall be 100 yards’, as did that of the Sheffield Association. The difference in dimensions was quantitative, not qualitative. What is more, and in contrast to the English soccer-style codes and the Melbourne rules, the RFU did not originally specify any measurements for the size of the rugby pitch. It was not until 1879 that an amendment was added to rugby’s ‘Laws of the Game’ that laid down that ‘the field of play must not exceed 110 yards in length nor 75 yards in breadth’.(23)

Cashman also points to the somewhat indeterminate nature of the early Melbourne football and the fact that ‘matches were sometimes held up so that players and officials could debate the rules’ as an example of the democratic nature of the Australian game.(24) Yet this too was no different to football in Britain, where disputes between captains over disputed points had become so common by 1870 that it was accepted practice to add time on to the length of a match to cover the time lost for play through arguments. As York rugby club captain Robert Christison admitted ’the more plausible and argumentative a player was, the more likely he was to be considered as a captain’. As in Australia, the referee or umpire was not initially part of either the rugby or soccer codes.(24)

Therefore, in the context of the ‘British world’ of sport, we can see that the set of rules developed in Melbourne in the 1850s and 1860s was simply one of many dozens of variations in the playing of football throughout the British Empire. As a correspondent to Bell’s Life in London wrote in 1861 ‘its rules are as various as the number of places in which it is played’. The Melbourne rules were no more indicative of Australian nationalism than the Sheffield FA’s rules were of an aspiration in the north of England for independence from the south.

Indeed, J.B. Thompson’s famous remark that the Melbourne rules would ‘combine their merits of both [Eton and Rugby football codes] while excluding the vices of both’ did not express antagonism towards British football but was merely an echo of the wider debate going on in British football circles about how to develop a common set of rules for all adult football clubs. Many sides in England had gone down the same path as the Melburnians; Lincoln FC for example described their rules as ‘drawn from the Marlborough, Eton and Rugby rules’.(25) The impetus for the drawing up of the Cambridge football rules in 1848 was also based on this desire to transcend the divisions between Eton and Rugby rules, and the formation of the Football Association in 1863 was based on an unsuccessful attempt to take the best from each variant to unify the football codes.(26)

Thus Wills’ alleged remark about developing ‘a game of our own’ had nothing to do with national pride but was just one more example of the commonplace frustration with the existing rules of football as played at the various public schools. With its code of rules Melbourne would now have a game of its own just like the English schools had games of their own, like Cambridge University had a game of its own and like Lincoln too had a game of its own.(27)

Notes

1 - Cashman, p. 43.

2- Eric Hobsbawm, ‘Mass Producing Traditions: Europe, 1870-1914’ in The Invention of Tradition, pp. 298-9.

3 - Quoted in Leonie Sandercock andIan Turner, Up Where Cazaly?, Melbourne, 1981, p. 33. Yorkshire Post, 29 Nov. 1886. See also W.F. Mandle ‘Games People Played: cricket and football in England and Victoria in the late-nineteenth century’, Historical Studies, vol. 15, no. 60, April 1973, pp. 511-35.

4 - Lionel Frost, Australian Cities in Comparative View, Penguin, Victoria, 1990, p. 4.

5 - Rob Pascoe, The Winter Game, 2nd Edition, Melbourne, 1996, pp.xiv.

6 - For the Sheffield FA, see Rules, Regulations & Laws of the Sheffield Foot-Ball Club, Sheffield, 1859, Brendan Murphy, From Sheffield With Love, Sports Books, 2007, pp. 37-41, and Adrian Harvey, Football: The First Hundred Years, London, 2005, . 11 and pp. 162-3.

7 - See Joseph Lennon, The Playing Rules of Football and Hurling 1884-1995, Gormanstown, 1997, p. 10.

8 - Robin Grow, ‘From Gum Trees to Goal Posts, 1858-76’ in Rob Hess and Bob Stewart (eds), More Than A Game, Melbourne, 1998, p. 21.

9 - C.W. Alcock (ed.) Football Annual, London, 1868, p. 74.

10 - Rule eight, reprinted in The Rules of Association Football 1863, Oxford, 2006, p. 49. John D. Cartwright, ‘The Game Playedby the New University Rules’, reprinted in reprinted in Jennifer Macrory, Running with the Ball, London, 1991, p. 164.

11 - Football Rules, Rugby School, 1845, p. 7.

12 - Percy Royds, The History of the Laws of Rugby Football, Twickenham, 1949, p. 6.

13 - RFU rules of 1871, reprinted in O.L. Owen, The History of the Rugby Football Union, London, 1955, pp. 65-72. Royds, pp. 7-8.

14 - Rule eight of the 1866 rules, in Geoffrey Blainey, A Game of Our Own, 2nd Edition, Melbourne, 2003, p. 225.

15 - ‘Bramham College Football Rules, October 1864 ‘ in The Bramham College Magazine, Nov. 1864, p. 182.

16 - Hibbins, ‘The Cambridge Connection’, p. 114. Thompson in the Argus, 14 May, 1860, quoted in Blainey, p. 45. For hacking in Britain, see Collins, Rugby’s Great Split, pp. 10-12.

17 - Richard Cashman, Sport and the National Imagination, Sydney, 2002, p. 45.

18 - See, for example, the reminiscences of Arthur Pearson in ‘Rugby as Played at Rugby in the ‘Sixties’, Rugby Football, 3 Nov. 1923.

18 - ‘Football Rules of 1862’ reprinted in Jennifer Macrory, Running with the Ball, London, 1991, p. 101.

19 - Pascoe, pp.xv-xvi.

20 - Blainey, pp. 49-50. Thomas P. Power (ed.)The Footballer: An Annual Record of Football in Victoria and the Australian Colonies, Melbourne, 1876, p. 126. NSWFL, The Laws of the Australasian Game of Football, Sydney, 1903 in the E.S. Marks Collection at the Mitchell Library, Sydney, shelfmark 728.

21 - For pitch dimensions see the respective rules reprinted in Blainey, pp. 222-4.

22 - For the FA and Sheffield FA, see C.W. Alcock (ed.) Football Annual, London, 1869, pp. 40-1. For rugby, Royds, p. 1.

23 - Cashman, p. 46.

24 - Tony Collins, Rugby’s Great Split, London 1998, p. 13.

25 - Bell’s Life in London, 8 Dec. 1861. J.B. Thompson in the Victorian Cricketers’ Guide, 1859-60, quoted in Hibbins and Mancini, p. 27. Bell’s Life, 21 Nov. 1863.

26 - Harvey, p. 48.

27 - ‘A game of our own’ was first attributed to Wills in the 1923 autobiography of fellow rule-framer H.C.A. Harrison, The Story of An Athlete, Melbourne, 1923, reprinted in Hibbins and Mancini, p. 119. For a broader discussion,see also Roy Hay "The Last Night of the Poms: Australia as a Post-Colonial Sporting Society' in John Bale and Mike Cronin (eds), Sport and Postcolonialism, Oxford, 2003, pp. 15-28.