-- This is the transcript of the keynote presentation I gave to the Rugby Union World Cup conference held in September 2015 at the University of Brighton.

In the beginning was the scrum.

The scrum is a common feature of almost all pre-modern football games. It was an essential part of the mass football games played between villages or districts, in which hundreds of men would struggle endlessly for possession of the ball.

But it was also a vital part of the types of football played at English public schools in the mid- nineteenth century, from which the modern football codes of association (soccer) and rugby are directly descended.

For example, at Eton school (which the sociologist Eric Dunning claims, in my view incorrectly, as the progenitor of soccer) there were two types of football, the wall game and the field game. The wall game resembles a continuous scrum played against a wall.

Eton Field Game 'Bully'

The Eton field game is more open, but the scrum - called a ‘Bully’ - is still a central part of the game. At Winchester school, again traditionally seen as an ancestor of soccer, the scrum, which is known as a ‘hot’ is also a central part of the game.

In fact, the scrum was common to all mid-nineteenth century codes of football, including American football, where it evolved into the scrimmage, and even Australian Rules, where it had died out largely by the 1880s.

The scrum at Rugby

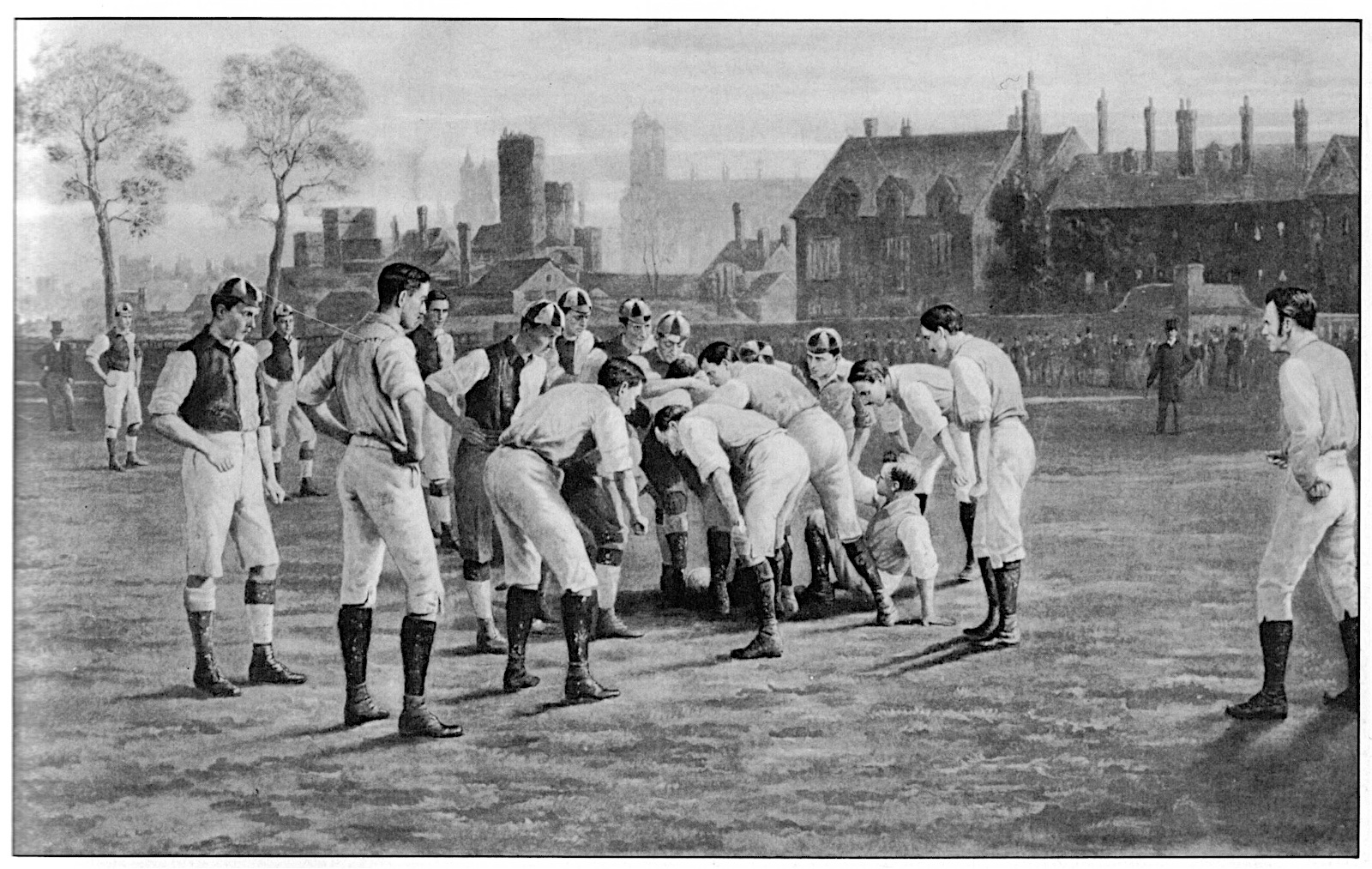

But in the football played at Rugby school, the scrum was the central feature of the game. As can be seen from the account of the game in Thomas Hughes’ Tom Brown’s Schooldays (published in 1857), rugby was a game of continual scrummaging. Play revolved around scrummaging and kicking to set up scrums. Handling the ball was severely limited and running with ball in hand was only permitted if the ball was bouncing when it was picked up - even a rolling ball could not be picked up by hand. At this stage in its development, it would not be accurate to describe Rugby football as a ‘handling code’ of football.

Most players took part in the scrum, with the aim of pushing the scrum towards their opponents’ goal or to the dribble the ball forward to the opposition goal line. Forwards in the scrum stood upright and pushed, kicking the ball or their opponents’ shins (‘hacking’). Putting one’s head down in a scrum was seen as an act of cowardice because it implied that that the player was concerned for his own safety.

A scrummage at Rugby School in the 1840s.

As in soccer, forwards were the attacking players and their role was to drive the opposing scrummagers as far back as possible and then capitalise on their disarray by dribbling the ball. Backs were the defensive players, whose role was to defend the goal or kick the ball to set up another scrum. The idea that the forwards would deliberately heel the ball out of the scrum for the backs would be seen as cheating, or even worse, as cowardice.

In 1871 the English Rugby Football Union was formed and it amended Rugby school rules to make the game more acceptable for adult players. For example it banned hacking and simplified scoring. But the scrum retained its importance. RFU secretary Arthur Guillemard described the workings of the scrum in 1877, explaining that as soon as the ball-carrying player was brought to the ground with a tackle,

the forwards of each side hurry up and a scrummage is instantly formed, each ten facing their opponents’s goal, packed round the ball, shoulder to shoulder, leg to leg, as tight as they can stand, the twenty thus forming a round compact mass with the ball in the middle. Directly the holder of the ball has succeeded in forcing it down to the ground, he shouts ‘Down’ and business may be commenced at once.

In this description one can see both the origins of American football’s use of the term ‘down’ for a completed tackle and the antecedent of rugby league’s play the ball rule.

But the centrality of the set-piece scrum to the early game inevitably led to problems. This was due to some extent to the fact that grown men were playing a game that had been originally developed by and for adolescent schoolboys. A scrum made up of varyingly sized youths was a very different proposition to one comprising heavy, mature men. Also, adult clubs were committed to winning and that meant that tactics were developed to ensure victory, or to avoid defeat at the very least.

The difficulties could be seen in this description of a typical scrum of the early 1870s by England and Richmond forward Charles Gurdon:

It would last, if skilfully manoeuvred (as we then thought), ten minutes or more, sometimes swaying this way, sometimes that; and on special occasions, when one side was much heavier than the other, this rotund mass would gravitate safely and unbroken, some thirty or forty yards towards the goal line of the weaker side, leaving a dark muddy track to mark its course.

‘Straight ahead propulsion’ was the primary tactic used in the scrum. Sometimes the most central forward would grip the ball between his feet while his fellow-forwards concentrated on pushing him through the opposing pack of forwards, allowing him to dribble the ball forward once they had broken through their opponents.

There were generally few opportunities for backs, not least because there were so few of them. In a team of fifteen or twenty, there would be two full-backs, two half-backs and one three-quarter, although two three-quarters gained popularity in the mid-1870s. The rest would be forwards. Passing the ball was extremely rare.

Reforming the Game

By 1875 these tendencies had brought rugby to an impasse:

How much longer are we to be wearied by monotonous shoving matches instead of spirited scrummages, and disgusted at seeing a 14 stone Hercules straining every muscle to move an opposing mountain of flesh a yard or two further from his goal-line, whilst he is all the time blissfully oblivious of the fact that ball is lying undisturbed at his feet

asked the London newspaper Bell’s Life.

To solve these problems, proposals were raised to lower the number of players in a team to fifteen. In 1875 the Oxford versus Cambridge varsity match was first played fifteen-a-side and the following season international matches became fifteen-a-side, although strangely the law was not formally changed until 1892.

The move to fifteen-a-side led to a number of structural alterations to the way the game was played. Scrums no longer lasted for minutes, because it was easier for the ball to come out of the scrum. Forwards now started to put their heads down in the scrum to see where the ball was. The frequency with which the ball now came out from the scrum meant that forwards began to look for opportunities to break away and dribble the ball downfield independently. And the danger of a forward breaking away with the ball at his feet meant that a third three-quarter had to be added in order to defend against the quick breakaway.

Moreover, and to the horror of traditionalists who tried unsuccessfully to persuade the RFU to outlaw the practice, teams began to deliberately heel the ball out of the scrum to the backs. Wheeling the scrum also emerged as a tactic, as teams with an extra player in the scrum, following the withdrawal of an opposing forward to the three-quarter line, realised that they could turn the weaker set of forwards around.

'A Match at Football: The Last Scrimmage' 1871.

Above all, the change opened the way for the development of the passing game. The speed with which the ball left the scrum and the ease with which forwards could peel away from the pack offered a quick-thinking half-back the chance to move the ball quickly out to his three-quarter or loose forward.

The process was helped significantly in 1878 when the rules were changed so that a tackled player was forced to release the ball immediately the tackle was completed. This meant that forwards now had to keep up with the play, rather than take their time to get to the scrum, increasing their fitness and expanding the available space on the field.

Facilitated by these rule changes and spurred by the tremendous growth in the popularity of the game, the 1880s became a decade of innovation. The Welsh invented the four three-quarter system and the scoring system was changed to allow points to be awarded for tries and goals - previously matches were won, as in soccer, by the team that scored most goals, regardless of tries.

In the north of England, Thornes. a team from a mining village near Wakefield, won the Yorkshire Cup in 1882, they did so thanks to revolutionary scrum tactics, such as using a wing- forward to protect their scrum-half, heeling the ball out of the scrum quickly, and allocating specific positions in the scrum and line-out to their forwards, anticipating the 1905 All Blacks by a generation.

But many of these changes were not welcomed by senior figures in English rugby. RFU president Arthur Budd regretted the increased importance of tries:

the very fact that try-getters are plentiful while goal-droppers are scarce shows that the latter art is very much more difficult of acquirement. Now this being so, why, I should like to ask, ought the more skilful piece of play to be depreciated, while a premium is placed on mere speed of foot?’

In 1896 he even proposed that heeling the ball out of the scrum should be made illegal.

On the other side were those who thought the changes had not gone far enough. In 1892, James Miller, the president of the Yorkshire Rugby Union, argued that rugby:

had now reached a period when another radical change must be considered, and that was the reduction of players from fifteen to thirteen. ... the end of the ‘pushing age’ had been reached and instead of admiring the physique and pushing power of those giants which took part in the game in the early stages, in the future they would be able to admire the skilful and scientific play of the game.

So, we can see the emergence of two different conceptions of how rugby should be played. Although the 1895 split in English rugby was caused by the issue of payments to players, it also broadly reflected this division over how rugby should be played.

Rugby League and the scrum

Within two weeks of the split, the Northern Union discussed moving to thirteen a side.The rationale, explained Leeds’ official Harry Sewell, was that

we want to do away with that scrummaging, pushing and thrusting game, which is not football, and that is why I propose to abolish the line-out and reduce the number of forwards to six. The football public does not pay to see a lot of scrummaging…

But his proposal to move to six forwards in thirteen-a-side teams was voted down, and over the next decade the number of scrums in rugby league grew dramatically. In 1899, in an attempt to get rid of messy rucks and mauls, the NU introduced a rule that if a tackled player could not release the ball, a set scrum had to be formed - an example of which can be seen below from the 1901 Oldham versus Swinton match.

These rule changes led to matches like Hunslet’s 1902 match with Halifax in which there were 110 scrums. In fact, the set scrum now had more importance in the rugby league game than in the rugby union. It was claimed by many that the excessive number of scrums in the game was turning young players towards soccer.

Eventually, in June 1906, the NU reduced the number of players to thirteen-a-side. And to solve the problem of endless scrummaging, it also introduced a new rule for playing the ball after a tackle. Now, instead of a scrum being formed, the tackled player was allowed to get to his feet, put the ball down in front of him and play it with his foot, usually to a team mate standing behind him.

This was a conscious decision to return to the modified principles of the original form of rugby scrum, whereby the tackled forward would place the ball down on the ground before the scrum commenced, albeit with only one opposition player directly in front of him.

Rugby Union and the scrum

The classic New Zealand 2-3-2 scrum formation.

After the split, the RFU was unchallenged in its ideas about the centrality of the scrum. But it was a different matter when facing teams from New Zealand and Australia. The 1905 All Blacks were heavily criticised for their seven man scrum and a free-standing wing-forward or ‘rover’, who fed the scrum and shielded his scrum-half to allow quicker passing of the ball from the base of the scrum. It was felt by many in England that the wing-forward was unsportsmanlike at best and downright illegal at worst.

The All Blacks’ forwards packed down in the scrum in a 2-3-2 formation, with two men in the front row, three in the second and two in the third, with the wing-forward where the scrum-half would traditionally stand at the side of the scrum. The system was believed to allow more focused pushing and also, because the scrum-half was protected, to facilitate quick ball from the scrum.

This method of opening up play from the scrum was very similar to that of the Northern Union, which in its first season had banned the defending scrum-half from going beyond his own front row until his opposite number had taken the ball from the scrum, thus providing more time to get the ball to the backs.

The controversy came to a head on the 1930 British Isles tour to Australasia. At an official dinner British manager James Baxter implied that Cliff Porter, the All Black captain who played as a rover, was a cheat. The fact that the British lost the test series 3-1 to New Zealand may also have exacerbated Baxter’s antipathy. On his return he had little difficulty in persuading the RFU to change the scrummage rules to effectively outlaw the wing-forward and the 2-3-2 formation.

Ironically, despite the RFU’s criticisms of All Black scrummaging methods, the England national side won four grand slams in the 1920s playing a power forward game inspired by the All Blacks. The architect of this success was William Wavell Wakefield, who brought a tactical planning to scrum play that had not previously be seen in English rugby union. The power of his teams was based on having back-rowers (known as ‘winging-forwards’ to distinguish them from the New Zealand detached roving wing-forwards) who could cover every inch of ground whether in defence or attack. Essentially it was the birth of the modern flanker.

But by the mid-1930s Wakefield’s innovations had led to matches became dominated by defensive back-row play. As Howard Marshall pointed out, ‘Defence overcame orthodox attack, and the decay of real scrummaging set in.’ The back-row forward had, he complained, ‘got somewhat out of hand’. The desire to receive or stop quick ball from the scrum led to interminable problems in putting the ball into the scrum, as front rows sought to stop their opponents getting the ball, and the keenness of the back-rowers to close down the half-backs led to constant penalties for off-side. The combination of back-row dominance and rule-changes designed to re-assert the centrality of the scrum meant that try-scoring dried up.

The game continued to be oppressed by forward domination and kicking throughout the 1950s. BBC radio commentator G.V. Wynne-Jones even called for the number of forwards to be reduced to six. The International Board made significant changes to the rules in 1954 to stop the deliberate collapsing of the scrum. It returned to the rules again in 1958, once more to reform the scrum and to speed up play through a variety of minor measures. But far from opening up the game, the IB reforms added to the problem, not least by significantly adding to the technicalities of the scrum.

It was not coincidence that the French, frustrated with their failure to win the Five Nations despite the strength of their club competition, finally found success in 1959 by emulating English forward play, rather than by playing the open game that supposedly marked the essence of the Gallic game. Scrum work, argued the French rugby writer Denis Lalanne, was the basis for winning rugby:

we know where rugby begins and where it must begin all over again. It certainly does not begin in the back row. It begins in the FRONT ROW. [emphasis in original].

And so it remained until the 1980s. The great French sides of the 1960s and 1970s were based on this very principal. But the advent of the World Cup and then professionalism gave rise to new problems that would undermine the centrality of the scrum to rugby union.

Modern League

The continuing importance of the scrum to rugby league can be seen in the fact that the first major gathering of rugby league officials after the First World War was a special conference in 1921 to discuss the problems of scrums. Not only was it felt that there were too many - with an average of between fifty and sixty a match - but hookers (a title which was just coming into common parlance, in preference to striker or centre-forward), props and scrum-halves were all criticised for refusing to obey the rules of the scrum.

The problem continued to occur throughout the interwar years. There were rule changes to prevent the more obvious reasons for scrum problems, such as the 1930 rule forcing forwards to pack down with three in the front row, two in the second row and a loose forward binding the second row - designed to prevent teams having four in the front row and unbalancing the scrum - and the 1932 ban on the hooker having a loose arm in the scrum.

But little changed and the debate became more intense in the late 1930s, when it was not uncommon again to see matches of between eighty and a hundred scrums. Indeed, rule-breaking was almost inherent in the very nature of the scrum - when former Wallaby hooker Ken Kearney arrived to play for Leeds in 1948 he asked a referee what were the best tactics to use in English scrums. ‘Cheat’ was the one-word reply he allegedly, but quite believably, received.

The seemingly never-ending cycle of clampdown, dismissals and eventual reassertion of the norm continued into the 1970s when the introduction of limited tackle rugby league in 1966 meant that struggle for possession, and consequently scrums, lost much of its previous importance. Indeed, the technical problems of the scrum were gradually solved by the expedient of allowing, albeit informally, the scrum-half to feed the ball to his own forwards.

In 1983 a handover of the ball to the opposing side, rather than a scrum, was introduced when the attacking side was tackled in possession on the sixth tackle. The final break with the past came with a series of changes in the early 1990s to the play-the-ball rule that removed the last vestiges of the struggle for possession and made it simply a device for restarting play.

Not the shape of things to scrum: Wigan v Bath 1996.

The future of the scrum

The advent of professionalism in rugby union in 1995 was accompanied by continuous attempts to improve the game as a spectacle, from the legalisation of lifting in the line-out to tinkering with the ruck and the maul in order to ensure quicker ball and more continuous play. The scrum has come under particular scrutiny.

I would argue that the reason for this intense scrutiny of the rules of the game, and especially of the scrum, is because professionalism has renewed rugby union’s evolutionary impulse. The impact of commercialism, a century after it had originally shut the door on radical change, is taking union down the same road that league has traveled.

League had evolved on a trial and error basis by providing answers to the traditional problems of those football codes that had emerged from the rules of football at Rugby School - just like American and other football codes. The problem of the breakdown, or what to do when the player with the ball had been tackled, had been solved by replacing the ruck or the maul with the orderly play-the-ball. Excessive touch kicking had been curbed by penalizing direct kicking into touch. The domination of the forwards had been diminished by reducing the number of forwards and cutting the opportunities for scrummaging.

Moreover, experience had led league to gradually abandon the idea of the struggle for possession of the ball, and thus reduce the importance of the scrum. As professionalism and the importance of winning had become paramount, it discovered, as union has begun to, that no matter how detailed the rules of the scrum or the breakdown, players and coaches would always find a way to circumvent or undermine them. In its place, league had evolved into a struggle for territory and position.

Rugby union is now faced with a paradox. The symbolism of the scrum has increased in the past two decades as many of its traditional shibboleths - such as amateurism - have disappeared. The supercharged collision of the two front rows to begin the scrum is itself a new phenomenon, unknown to earlier front rows, for whom the struggle would begin as the two packs bound themselves together.

Yet, ironically, the importance of the scrum to the playing of the modern game is rapidly diminishing. In the 2011 Rugby World Cup the average number of scrums per match was just seventeen, compared to twenty-seven in the 1995 tournament and thirty-one in internationals staged in 1983. The 2015 6Nations and 2014 Rugby Championship saw just 12 - roughly the same number as in league. Moreover, the ‘contest for possession’ is also steadily declining in importance - the leading international sides now retain possession at the scrum and the line-out 85%-90% of the time. In 2005, the IRB discovered that the side in possession retained the ball thirteen out of fourteen times at the breakdown.

What’s the solution to the problem of the rugby union scrum? More yellow cards for scrum offences? Already tried in RL - and failed.

There is no answer - the scrum will whither, but it will not die. Rugby of both codes is too rooted in its traditions, culture and belief systems. Logic is not necessarily a determining factor in rugby decision-making. But the importance of the scrum will continue to decline, until it becomes, like the human coccyx, an almost redundant vestigial reminder of the evolutionary past of rugby, and indeed of all football codes.