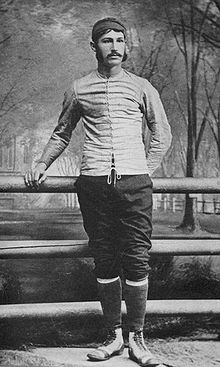

Walter Camp in 1878

This is the third article in a short series on the history of the rugby codes in North America. It looks at the origins of American football and its ‘creation myth’ of Walter Camp’s invention of a uniquely American game. The idea that American football was invented by Walter Camp is still widely believed by fans and academics alike, but is based on a misunderstanding of how rugby developed. For a more detailed discussion of the birth of American football, see my ‘Unexceptional Exceptionalism: the origins of American football in a transnational context’ published in the Journal of Global History in 2013.

Just like the William Webb Ellis legend, American football developed its own ‘creation myth’. In the same way that the Webb Ellis story painted a picture of a sport that owed everything to the public schools that supplied the the RFU with its leaders, American football’s tale emphasised how uniquely American its game was.

The story revolves around Walter Camp. He went to Yale University in 1875 and became the starting half-back for the university rugby team. But, so the story goes, he was dissatisfied with the rules of the game. He thought they were too vague and based on British traditions that were inappropriate for the ‘New World’. In particular he thought the scrum was distinctly un-American, writing in 1886 that:

English players form solid masses of men in a scrummage and engage in a desperate kicking and pushing match until the ball pops out unexpectedly somewhere, leaving the struggling mass ignorant of its whereabouts, still kicking blindly where they think the ball may be.

To get rid of this problem, in 1880 he proposed that the scrum should be abolished and in its place the two sets of forwards lined up opposite each other. He invented the ‘snap’ when the ball is handed back to the quarterback to make the game less chaotic. Eventually the forward pass was introduced.

But this tale of how Camp invented American football is its own scrummage of fact, fiction and supposition. The historical record is not that quite straight forward.

The first and most glaring problem is that, when it came to playing rugby without a scrum, the Canadians got there first.

In October 1875, a full five years before Walter Camp proposed abolishing the scrum in America, the first Canadian rugby enthusiasts had proposed precisely the same thing at a ‘Football Convention’. Nine clubs met to discuss the rules of the game in Toronto and decided to adopt the rules of the RFU. But three clubs voted against. These clubs essentially wanted to play rugby without the scrum. Eventually the reformers, led by McGill and Toronto universities, won the argument, and rugby in Canada began its evolution towards gridiron-style Canadian football.

Back in the USA, when Columbia, Harvard, Princeton and Yale students met in November 1876 to found the Intercollegiate Football Association (IFA) and agree a common set of rules, they adopted the RFU rule book including the scrum rules.

But arguments still raged between the elite football-playing universities of the U.S. east coast. The big debate was about the number of players in a team. The first IFA meeting voted for 15-a-side but Walter Camp’s Yale wanted 11-a-side. They had played 11-a-side teams ever since 1873 when a team of footballers from Eton College visited from England. Yale unexpectedly won the match, which was played under a hybrid set of rules.

The Yale men’s surprising success convinced them that eleven men were all that were needed to play the game. Eventually in October 1880 the other universities agreed to Camp and Yale’s proposal. Rugby in America became an 11-a-side game.

This move to eleven players fundamentally changed rugby. With just six or seven forwards, instead of the normal nine or ten found in a fifteen-a-side team, a traditional rugby scrum was impossible. In rugby at this time, the aim of the forwards was not to heel the ball backwards but to dribble it forward through the opposing pack. Opponents could line-up several columns deep, preventing headway from being made for considerable periods.

However, with fewer opposing forwards, dribbling the ball forward resulted in it quickly emerging out on the opponents’ side, giving them use of the ball to set up their own attack. Conventional scrummaging was completely counter-productive. Yale and the other teams playing eleven-a-side rugby therefore began to line their forwards up in a single line, which became known as the ‘open formation’, so that they could heel the ball behind them to their backs as quickly as possible.

At the same time that teams were reduced to eleven, the ‘snapback’ - where the ball was passed backwards to the quarterback (itself the Scottish rugby term for the scrum-half) - was introduced. Two years later in 1882, the ‘downs’ rule was introduced, which gave a team three ‘downs’ to get the ball five yards upfield or hand it over to the other team (later increased to four downs and ten yards).

True believers of the Walter Camp myth believe these changes were uniquely American. But similar changes would take place in Canadian rugby and in rugby league. Even blocking, which allowed players without the ball to be tackled, was not unknown in the early days of rugby and was used by Blackheath and at Rugby School itself. There was nothing specifically American about the way Walter Camp changed rugby. Even as late as December 1893 the New York Times could still call the American game ‘rugby’.

What did make the game uniquely American was not one of Walter Camp’s innovations at all. It was the legalisation in 1906 of the forward pass. Introduced to open the sport up and reduce its defensive brutality, more than any other change it was this that gave American football its distinctive character. Camp, by this time dubbed ‘the father of American football’, remained agnostic on this fundamental change that marked the definitive passage of rugby into American football. The gridiron game was now truly an American game, yet its origins lay not in the head of Walter Camp but in the debates about how to play rugby football that took place throughout the English-speaking world in the second half of the nineteenth century.

- - The full story of the fate of the rugby codes in North America is covered in my forthcoming book The Oval World.