On 16 November I gave the after-dinner speech to the annual dinner of the UK’s Parliamentary Rugby League Group to mark the 120th anniversary of the founding of the Northern Union. This is a transcript of my remarks:

"A Northern Union man all the way through."

We’re here to celebrate 120 years of rugby league, so I thought I’d start with a few quotations from what some people have said about the sport over the past century or so:

‘Rugby league is heading down the path to extinction.’ Sydney Daily Telegraph journalist, Rebecca Wilson in 2010.

‘Great game, rugby league, such a shame it has to die.’ - Frank Keating in the Guardian in 2001.

‘The game of rugby league itself will die.’ - John Reason and Carwyn James in The World of Rugby in 1979.

‘Rugby League is dying.’ - Former All Black captain and NZ MP Chris Laidlaw in 1973.

‘it is still dying.’ Daily Telegraph [London] in 1954 after the first rugby league world cup.

‘Rugby à Treize est mort.’ L’Auto in 1940.

‘Is rugby league doomed?’ Sydney Daily Telegraph (again!) in 1934.

‘Rugby League will be a nine day wonder.’ Sydney's The Arrow, 3 August 1907, when AH Baskerville's All Golds arrived in Sydney.

‘In a year or two, the Northern Union will almost be forgotten.’ Pall Mall Gazette, 30 September 1895, less than five weeks after the meeting at the George Hotel in Huddersfield that formed the Northern Union!

Well, rugby league is still here - and in extremely rude health. Today the game has 36 nations affiliated to the Rugby League International Federation; domestically it is played in every county in England. Even these barest of statistics would be beyond the comprehension of the men who formed the Northern Union at the George Hotel in August 1895.

The game they created has survived despite facing a level of hostility unique in world sport.

For a hundred years the rugby union authorities banned union players from playing rugby league - those that did were banned for life. The game wasn’t played in universities until 1968 and was not recognised by the armed forces until 1994. It was banned in France by Marshall Petain’s collaborationist Vichy government during World War Two.

Even today, as the arrest of rugby league organised Sol Mokdad in the United Arab Emirates demonstrates, rugby league pioneers sometimes face obstacles undreamt of by other sports.

Yet despite such obstacles the game goes on and is stronger than ever.

Why?

Most importantly, it’s a thrilling and spectacular athletic contest. Even before the split in 1895, the northern clubs placed a premium on handling, passing and running with the ball. The scoring of tries - rather than goals - became the object of the rugby league. And it has never been afraid to innovate to ensure that the sport remains ‘a game without monotony’, as Hull official C.E. Simpson put it when teams became 13-a-side and the play the ball the ball was introduced in 1906.

And rugby league has led the way for other sports too, introducing floodlighting, substitutes and Sunday matches before soccer or rugby union. The game was importing stars from around the world in the 1900s - stars like Albert Rosenfeld at Huddersfield, Lance Todd at Wigan and Jimmy Devereux at Hull were adding cosmopolitan glamour to rugby league decades before Premier League became a destination for soccer’s global stars.

The sin bin and video ref - staples of many sports today - were pioneered in rugby league. And it was the second major sport after soccer to organise a world cup tournament when the first-ever Rugby League World Cup was held in France in 1954.

But I think that the game has survived and expanded around the world for more than just what happens on the pitch.

Because what makes rugby league so unique is that it is a sport founded on a principle. The Football Association was created to draw up a common set of rules for all football clubs. The RFU was founded to standardise rugby rules and organise international matches. The MCC was founded to play cricket, and to regulate gambling on the game.

But the Northern Union was founded on the principle of equal opportunity for all - that everyone should be allowed to play rugby to the highest level of their ability, regardless of their school, their status or their social background.

The clubs that met at the George Hotel in August 1895 legalised broken-time payments because they felt that it was the only way that players who spent their working week in a factory, on the docks or down a mine would be able to play on equal terms with the doctors, lawyers and accountants who played for socially elite clubs. No-one, felt the Northern Union pioneers, should lose wages in order to play the game they loved.

This principle of equality of opportunity has been at the heart of rugby league ever since 1895. It was what drew the rugby players of Australia and New Zealand to start rugby league down under in 1907 and 1908. It was the principle that Jean Galia and his fellow pioneers followed when they established rugby league in France in the 1930s.

And it has meant that rugby league welcomed black players into the game at a time when other sports had turned their backs on them. George Bennet was capped for Wales in 1935, fifty years before Glen Webbe became the first Welsh black union international. Jimmy Cumberbatch was capped for England in 1936, forty years before Viv Anderson became England’s first black soccer international. And when Clive Sullivan lifted the RLWC trophy for GB in 1972, he did so as the first black captain of a British national team in any sport.

And while no-one would claim that the sport is free of prejudice or chauvinism, it has also a notable record of women’s involvement, from supporters’ club officials in the 1930s, to the women’s teams that played in Workington in 1954 to Julia Lee becoming the first senior match official in any football code in the 1980s.

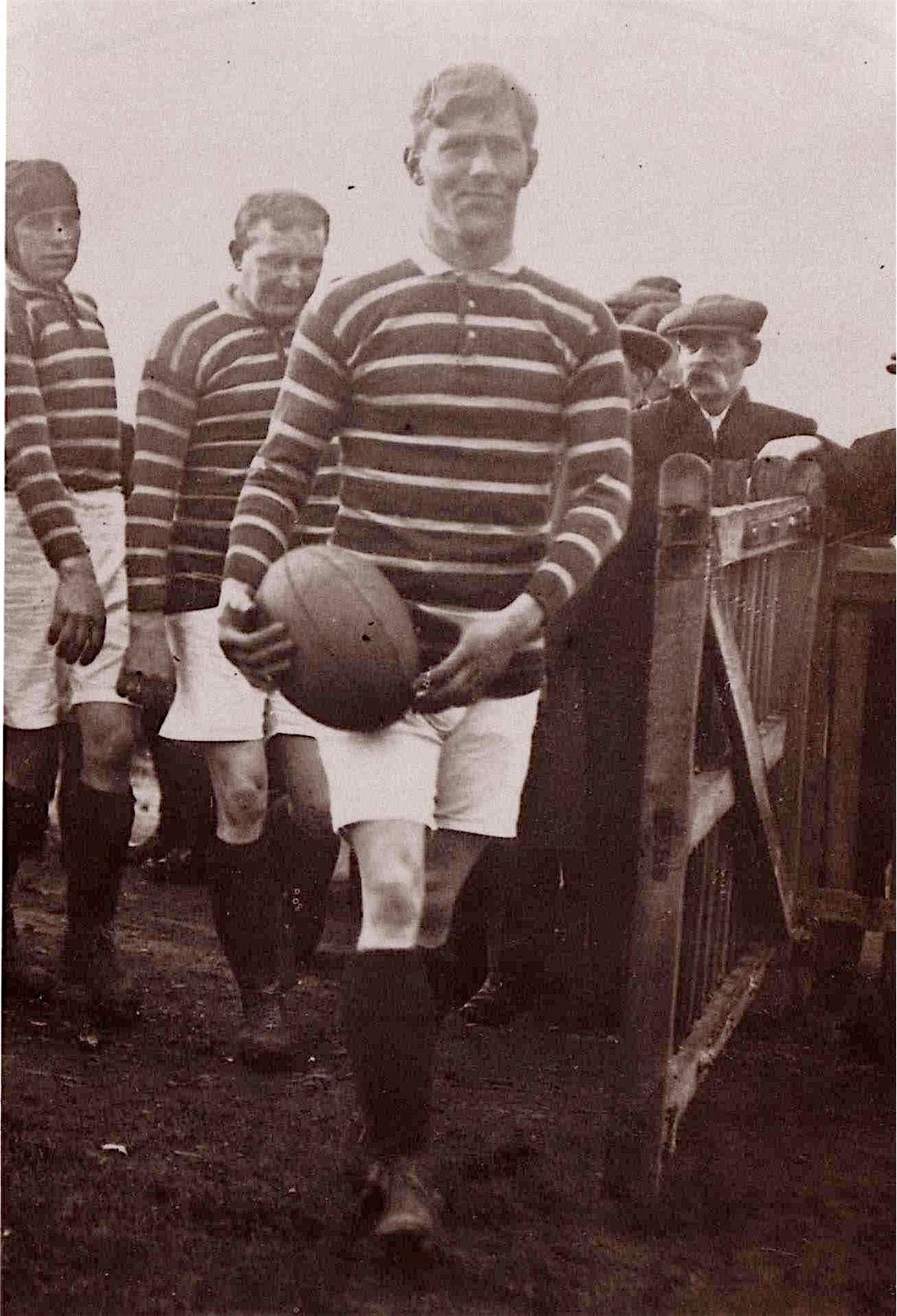

But this principle of equality of opportunity has also allowed working-class people could play a leadership role in society. So in 1910, the first Northern Union touring side to Australia and NZ was led by Jim Lomas, a docker. The 1914 tourists were led by Harold Wagstaff, a delivery driver.

Until relatively recently, outside of the trade unions, working people did not hold leadership positions in society. Nor until the 1960s did they usually travel abroad, unless in the armed forces or as emigrants.

For a docker and a driver to lead a group of men to a country 14,000 miles away was therefore unprecedented. Until the 1950s cricket sides were always captained by privately-educated amateurs, and the England soccer side didn’t even play in the world cup until 1950, let alone tour other countries.

This, I suspect, goes some way to explaining the popularity of rugby league in Australia and the industrial regions of New Zealand - they could identify with British teams because the tourists were people just like the mass of ordinary Australians and Kiwis.

So rugby league’s strength has always been about more than the thrilling spectacle on the pitch. At its heart was the principle that ordinary people should have the opportunity to develop their talents to their fullest extent.

When Harold Wagstaff wrote his autobiography in the mid-1930s he began with the words: ‘I am a Northern Union man all the way through’.

This was more than a declaration of mere sporting affiliation. It was a acknowledgement of pride in the achievements of not just himself, but of a sport that allowed working-class men like him to develop their talents to the full and to take their place at the head of their communities.

And to that extent, 120 years after the historic decision to breakaway from the RFU was made, we should all be Northern Union men and women today.