Every time there's a major rugby union event in England, the press roll out the old cliche about 'rugby union no longer being the preserve of the middle-class'. There was a laughably fact-free discussion along these lines on BBC Radio 4's The World Tonight (starts 30 minutes in) on the eve of the world cup kick-off.

More interesting was Bed Dirs' article on the BBC Sport website, Is English Rugby Union Just For Posh Kids? which makes the point that 61 per cent of top-level English rugby union players went to private schools (67 per cent of the current England world cup squad are privately educated), as opposed to just 6 per cent of elite English soccer players. The figure for rugby league would be even lower. The percentage of the general population who go to private school is 7 per cent.

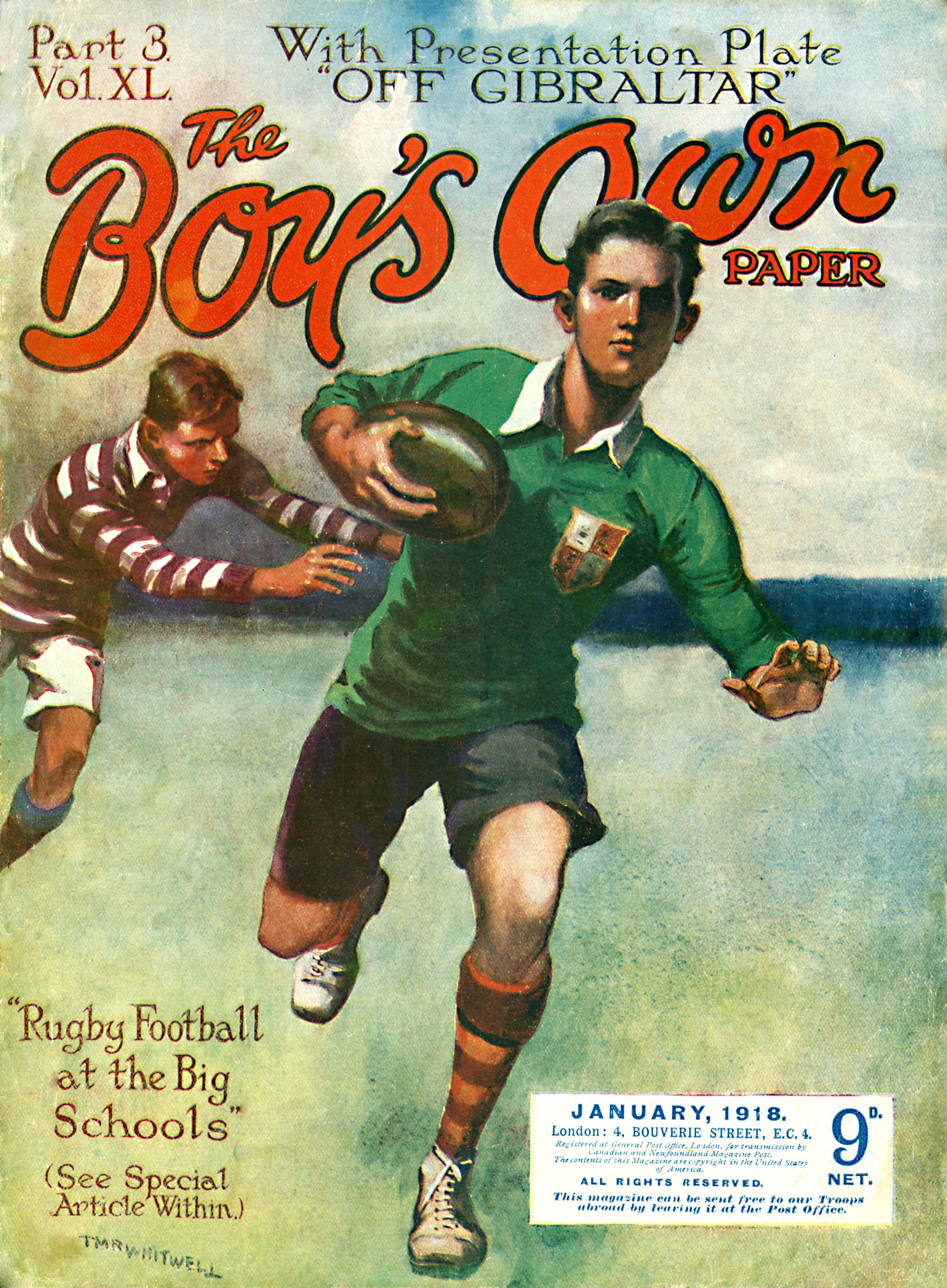

'Rugby Football at the Big Schools'. In 2015 as in 1918?

Defenders of the idea that rugby union is classless often argue that some of these players - it is never stated how many - originally went to state schools but were later given scholarships by private schools to play rugby there. This is undoubtedly true.

But this merely shows just how deeply rugby union is part of the middle-class world of private education. A cohort representing 7 per cent of the population occupy over 60 per cent of the places in the England squad - this makes the England more 'middle-class' than Oxford or Cambridge universities!

More to the point, when was the last time a teenage soccer player was sent to a private school to improve his football skills and enhance his chances of playing for England? My guess would be never.

But this should come as no surprise. Historically speaking, the social composition of rugby union has barely changed, as you can see in the following analysis of the social and educational backgrounds of England internationals between 1871 and 1895 that appeared in chapter five of A Social History of English Rugby Union (needless to say, the chapter goes into much more detail than this blogpost allows):

"Between the first international in 1871 and the advent of professionalism in 1995, 1,143 players were selected to play for England. We know the schools attended by 876 of them. The number of internationals who attended elementary, board, secondary modern or comprehensive state schools was just 66, not a significantly larger number than the 47 who were educated at Rugby School itself.

This leaves 810 who were educated at grammar or fee-paying schools. Of these, 155 went to schools identifying themselves as grammar schools, although this self-definition includes both independent fee-paying schools and state-funded secondary schools, leaving 655 who were unambiguously privately educated. In other words, 92.4% of all England internationals for whom we have school details went to fee-paying or grammar schools.

Of course, there were also players who had originally attended non-fee paying schools but won academic or athletic scholarships to private or grammar schools. Working-class scholarship boys such as Ray French and Fran Cotton featured especially in England sides of the late 1950s to the mid-1970s. But unfortunately there is no data available that would help us quantify their number. It is also the case that the social mobility of this period that was opened up in large part by educational opportunity proved short-lived and was certainly in decline by the mid-1990s.

We could therefore assume that this group would not significantly alter the overall picture. Moreover, the phenomenon of the rugby-playing ‘working-class scholarship boy’ highlights the fact that rugby union was part of the acculturisation process through which talented young students were assimilated into the middle class, rather than rugby union becoming ‘classless’ and moving down the social ladder in its appeal, as was the case with soccer.

What about the players whose schools we do not know? Of these 267 players, 25 attended university, medical school, naval academy or the Royal Indian Engineering College. We know that 68 of those for whom we have no educational data had what can be termed ‘middle-class’ jobs, ranging from sales managers and accountants to company directors and, in the case of John Matters who played for England in 1899, a rear admiral in the Royal Navy. And of those for whom we have neither educational nor occupational data, 15 played for socially-prestigious elite clubs such as Blackheath, Manchester or Richmond. This would indicate another 108 players that could be categorised as being clearly from the middle classes.

What of the remaining 159 players? There are 55 for whom we know only the name of the club for which they played. They played for clubs in the midlands, south-west or pre-1895 north that traditionally had a socially-mixed, cross-class playing personnel, making it impossible to draw any inference about their social background from their club. This leaves us with 104 players whose schools we do not know but who are recorded as having manual occupations, beginning in 1882 when storeman Harry Wigglesworth of the Yorkshire club Thornes made his debut.

The most common employment was that of publican, which provided gainful employment for 22 England internationals. Becoming a pub landlord was invariably an inducement to a player to stay with a club or to join a new one, offering an attractive way out of direct manual labour. Thirteen of these publicans became rugby league players. Indeed, 38 of the 104 manual workers went on to play league. The only other significant manual occupational groups were thirteen police constables and eight ship and dockyard workers who played for clubs on the south-west coast and were employed mainly in naval dockyards.

We can therefore say that of the 1,088 England players for whom we have verifiable educational or occupational information, only 170 (or 15.6%) were unambiguously not part of the middle classes, either because they attended non-private or grammar schools or were employed in manual labour."