I’m very pleased to announce that my new book How Football Began: A Global History of How The World’s Football Codes Were Born will be published on 1 September by Routledge. The title tells you all you need to know about what’s inside - but if you’d like a flavour of what to expect, here’s a quick rundown of each chapter.

UPDATE! Routledge are now offering a 20% discount on pre-orders of the book. Simply click here and enter the code FLR40 at the checkout.

1. The Failure of the Football Association

The Football Association was created in 1863 to unite England’s fledging football clubs under a single set of ‘universal rules’. It failed, creating a rulebook that was continually disputed and revised, and alienating many clubs who would go on to form the Rugby Football Union in 1871. Far from marking the start of soccer’s inexorable rise to popularity, the early FA did little to popularise the sport, and would play second fiddle to the RFU for the next two decades.

2. Before the Beginning: Folk Football

Propelling a large ball to a goal with the hand or foot has been a feature of almost every human society. In pre-industrial Britain, football of varying types was played extensively. Yet this was a recreation that was intimately connected to the rhythms and traditions of rural life, and had no substantive continuity with the modern forms of the game that emerged in the mid-nineteenth century. It would take the industrial revolution of the Victorian era to give birth to football in its modern guise.

3. The Gentleman’s Game

The first football clubs of the modern era emerged as part of the growing business and recreational networks of young middle-class men who had learnt the game at school, and who sought to bring the spirit of Muscular Christianity - as popularised due to the 1857 publication of Tom Brown’s Schooldays - to their new world of leisure. Like their equivalents such as the East India Club (1849) and the Hurlingham Club (1869), these were exclusive clubs that had no interest in popularising their sport. Nor did they bother too much about the rules of football; for these young gentlemen, the game was the thing.

4. Sheffield: Football Beyond the Metropolis

The emergence of football was not restricted to the metropolis. In Sheffield, and to a lesser extent Nottingham, the strength of local cricket culture provided the basis for the growth of a new football culture that was based on local rivalry, regular competition, and growing media interest in the sport. Although claims that Sheffield was the true birthplace of soccer have come to resemble rugby’s William Webb Ellis myth - indeed, many of Sheffield’s rules were drawn from those of Rugby School - the outlines of modern football culture can first be discerned in Sheffield and Nottingham.

5. The End of the Universal Game

By 1870 it was clear that the FA’s desire for a universal football code for all clubs was not feasible. The growth of rugby football had oustripped soccer all over Britain. In response, the FA’s new secretary, C.W. Alcock, initiated an England versus Scotland match and in 1871 began the FA Cup tournament. Clubs were increasingly forced to make a choice between one or other code. When the rugby clubs responded in 1871 by forming the Rugby Football Union (RFU), football was irrevocably split.

6. From the Classes to the Masses

As the profile of association and rugby football grew due to the popularity of cup competitions, it began to find an audience beyond the world of middle-class young gentlemen. Cup tournaments turned clubs into representatives of local communities. The increased leisure time and spending power of the working classes drew them to football as spectators and players. In major industrial cities such as Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds and Cardiff, football of whatever code soon became the passion of the masses.

7. Glasgow: Football Capital of the Nineteenth Century

Nowhere was the enthusiasm for football so strongly expressed or so intimately wound up with the life of the city as Glasgow. By the early 1880s, the city probably had more players, more clubs and more spectators than anywhere else in Britain. Such was the importance of soccer to Glasgow that by the early 1900s it had three stadia that could hold more than 100, 000 people, just under half of its population. Glasgow would establish the template of the football city that would be replicated in the twentieth century in Barcelona, Milan, Buenos Aires and Rio de Janiero.

8. The Coming of Professionalism

The burgeoning popularity of association and rugby not only brought spectators flooding in but also saw unprecedented amounts of money come into the game. Increased rivalry for cup success also meant that clubs sought to attract the best players and by the end of the 1870s both soccer and rugby were paying players. Faced with a revolt from its northern clubs, in 1885 the FA legalised professionalism and three years later the leading professionals clubs formed the Football League. But in rugby, the RFU decided that soccer’s experience was not for them and banned all payments to players. It was a fateful decision.

9. Women and Football: Kicking against the Pricks

Modern football in all forms was created as a sport for young men that would guard against effeminacy and homosexuality. Women were not welcome. But women still wanted to play the game. After a series of commercially-driven false starts to women’s soccer in the 1880s, the 1895 Lady Footballers’ side captured the spirit of the ‘New Woman’ movement. But it wasn’t until World War One that women’s football became a mass sport - and its promising beginnings were snuffed out as post-war reaction forced women out of the factories and back into the homes as wives and mothers. It wouldn’t be until the 1960s that the women’s liberation movement and the enthusiasm of working-class women once more mode football a viable option for the majority of women.

10. Rugby Football: A House Divided

Soccer’s professionalism and its league system launched it to unimaginable popularity. Rugby lost its early advantage and the RFU’s insistence on the strictest amateurism plunged the sport into civil war. Players were banned and clubs suspended. Clubs in the north, were rugby still rivalled soccer in popularity, argued for ‘broken-time payments’ two be made to working-class players who took time off work to play the game. The RFU rejected the demand decisively and in the summer of 1895 the top clubs in the north decided that enough was enough, and broke away to form the Northern Union.

11. Melbourne: A City and Its Football

Rugby had always seen itself as the game of British imperial nationalism, and thanks to ‘Tom Brown’s Schooldays’ it spread across the English-speaking world. Nowhere was this more true than in Australia and especially in Melbourne. Barely two decades after the city had been founded, young middle-class men in the city had adapted rugby rules to create their own football code, which would become known as Australian Rules. Nowhere else was a code and a city so intertwined. Yet far from being a symbol of Australian separateness, Melbourne football was no less a symbol of Britishness than anywhere else in the British Empire.

12. Australian Rules and the Invention of Football Traditions

All sports have their done creation myths and invented traditions. Most famously, rugby has William Webb Ellis. Australian Rules is a unique laboratory to see how changing ideas about national identity are reflected in narratives about the origins of football. From being a proudly British sport until the end of empire in the 1950s, to imagining that it was derived from Gaelic Football in the turbulent 1960s and 1970s, to believing that it originated in Aboriginal ball games in the liberal era of the early twenty-first century, the mythology of Australian Rules highlights how football mirrors the shifting nature of national politics.

13. Ireland: Creating Gaelic Football

While the other football codes prided themselves on being British or, in North America, part of Anglo-Saxon culture, huge numbers of football followers in Ireland rejected Britishness as the enemy of the Irish people. But there was no native football Irish football code that could offer an alternative to soccer or especially rugby. So the founders of the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) had to create their own code of football from scratch. Rejecting rugby, they took from different codes but were able to establish Gaelic football because of the GAA’s close links to its local communities and Irish nationalist, religious and cultural networks.

14. Football and Nationalism in Ireland and Beyond

Gaelic football was the only code of football that rejected its identity with the British world. Yet the leaders of the GAA accepted the Muscular Christian framework of sport, substituting Irish nationalism for British nationalism. Its nationalism seemed more overt only because it was cut against the prevailing attitudes of other football codes. In reality, they too were no less nationalist or militaristic than the GAA. All football codes were closely linked to the military and embraced an ideology of racial and national superiority, links that would become stronger and reach their apotheosis in World War One.

15. American Football: The Old Game in the New World

Football in America began as rugby but, as in Australia, Ireland and much of the rugby-playing world, soon broke from what Americans saw as the limitations of the rugby game. The game evolved rapidly, moving to eleven-a-side and abandoning the scrum, yet this was no more an expression of ‘American exceptionalism’ as later historians would claim than the changes to rugby's rules elsewhere. Thanks to the tight control of the Ivy League universities, college football quickly became a mass-spectator, but not a mass-participation, sport.

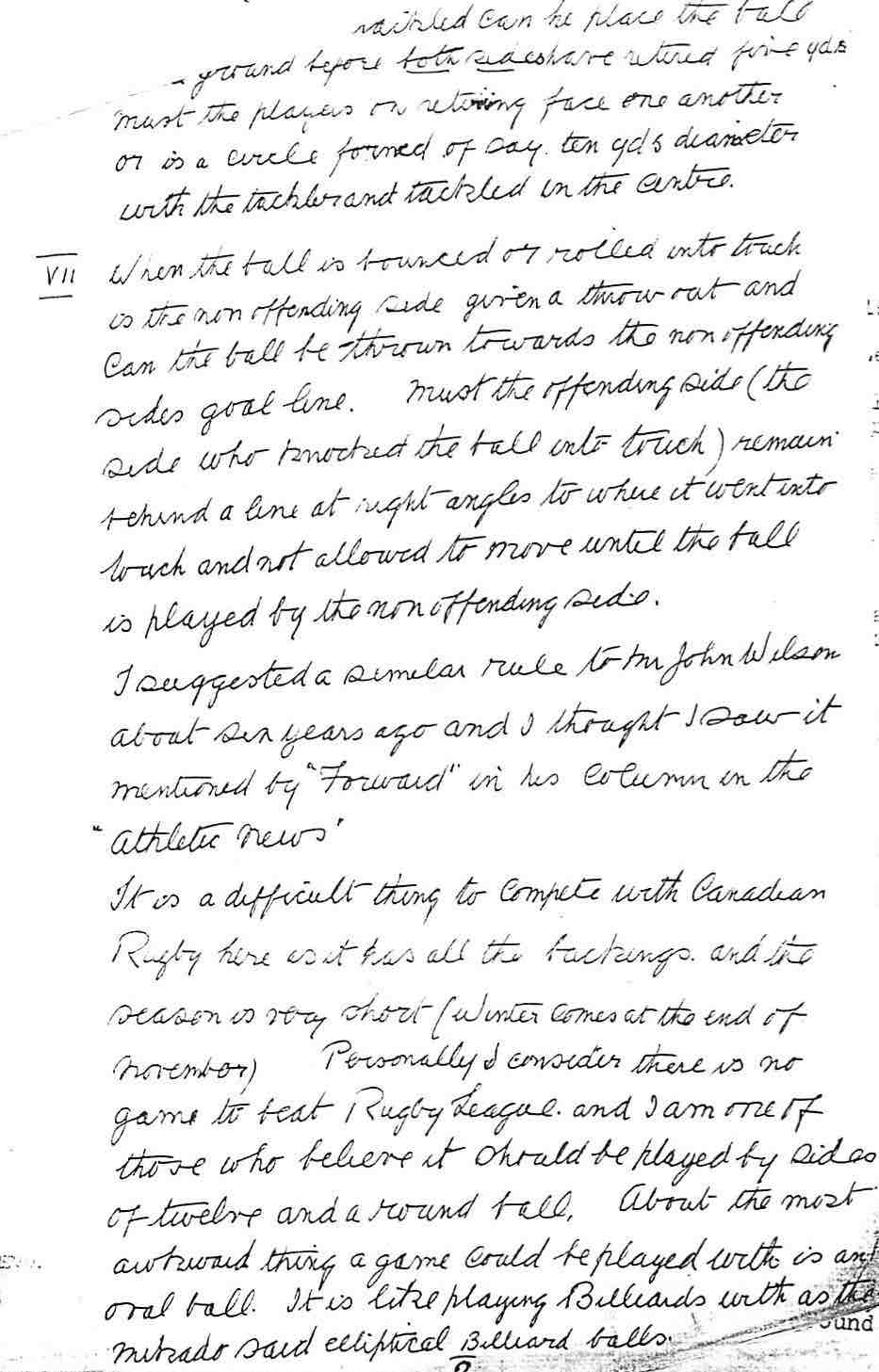

16. Canadian Football: Between Scrum and Snapback

As a loyal member of the British Empire, Canada embraced football in its rugby form in the 1860s and 1870s. Yet its proximity to the United States exerted constant pressure on its sporting choices. In the 1870s rugby footballers in Ontario anticipated developments in American football by developing a scrum-less form of rugby, but its loyalty to British conceptions of football prevented it from breaking completely with rugby rules. It would not be until the 1900s that Canadian football emerged as a distinct sport in its own right, somewhere mid-way between British rugby and American football, reflecting the political and cultural position of Canada itself.

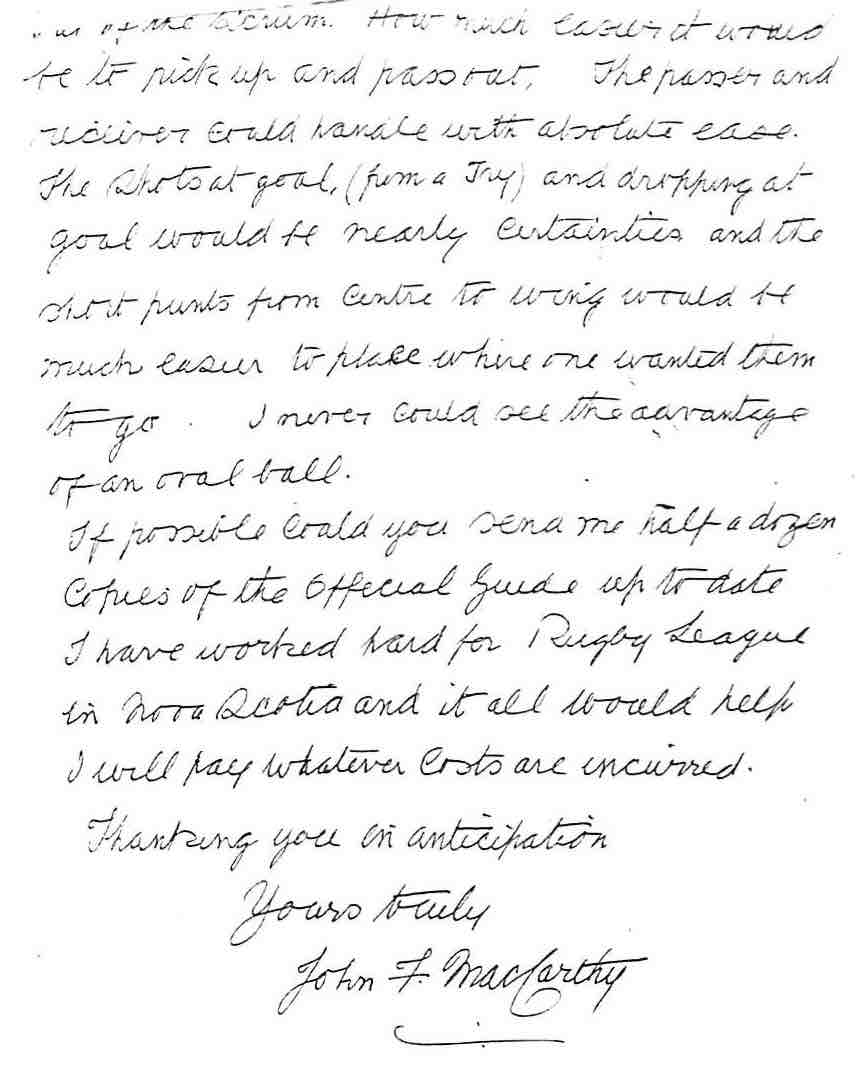

17. Rugby League Football: From a People’s Game to a Proletarian Sport

Rugby’s 1895 split cleaved the sport along class lines, and the Northern Union, which became the Rugby Football League in 1922, quickly became rooted in the industrial working-class communities of northern England. It changed the rules of the game to make it more attractive, paid its players and created the league and cup competitions that the RFU had opposed. All of these developments had been discussed in rugby before the split, and represented an alternative road for mass-spectator rugby. Yet the hostility of the RFU, which ostracised anyone connected with the league game, and the juggernaut of soccer’s popularity, initially locked the sport into its heartlands.

18. The 1905-06 Football Crisis: North America

By legalising professionalism in 1885, soccer had freed itself from the problems that would plague the other football codes. By the mid-1900s, American and Canadian football has been consumed by controversies over commercialism, professionalism and the violence of the game. The president of the United States intervened and many leading university administrators called for the abolition of football. Top west coast universities switched to rugby. Faced with this existential threat, football reformed its rules to make it safer, which included legalising the forward pass. Yet it did nothing to resolve the issue of money in the sport, and established a system of amateur hypocrisy that still prevails today.

19. The 1905-06 Football Crisis: Rugby

The problems of commercialism and professionalism did not leave rugby after the 1895 split. Wherever rugby was a mass spectator sport, especially in Australia, New Zealand and Wales, the game became engulfed by these problems. When the all-conquering 1905 All Blacks returned home, they became they lightening rod for player discontent, and in 1907 a professional rugby league New Zealand side toured Britain. In Australia, a simmering player revolt came to a head the same year and rugby league quickly gained ascendency. In Wales, rugby league clubs were established in the Welsh rugby heartlands but proved to be short-lived - yet rugby’s global crisis had changed the game forever.

20. Soccer: The Modern Game for the Modern World

Soccer’s embrace of professionalism fundamentally changed the nature of the game. Unlike the rugby codes which still largely retained amateur rules and administration, soccer could now claim to be a meritocratic game, open to any male with the talent to play. This proved to be extremely appealing to the middle-class young men of Europe and South America, who saw soccer as an expression of modernity and universalism. Many rejected their own national traditions of gymnastics to embrace the game, and, keen to promote it regardless of the indifference of the British soccer authorities, would found FIFA in 1904.

21. The Global Game

While British engineers, merchants and educationalists would take soccer around the world, they were not the people who popularised it. Many British expatriate communities abandoned soccer as it became popular among the local population, choosing rugby for its exclusivity, and the driving force behind soccer’s exponential growth in the non-English speaking world became the local middle-classes who sought not only recreation but also a means of expressing a newly-developing national identity. Soccer had become the global game by breaking the link with its British inventors.