- - On 14 April I gave this paper at Harvard University's 'Soccer as a Global Phenomenon' conference. It was a genuinely international and interdisciplinary gathering that brought together scholars from around the world. Below is that paper I gave, which is based on a larger forthcoming piece of research about the global expansion of football of all codes in the late Nineteenth Century.

How and why did soccer become the global game? There have been numerous studies of soccer as an existing globalized sport but very little exploration of the historical roots of how soccer actually globalized. The game path to globalisation has invariably been portrayed as a smooth and seamless rise from its origins in mid-nineteenth century England to today’s undisputed ‘world game’. Yet this unproblematic view of soccer history ignores the complex early history of the sport and particularly the struggle for football hegemony between the Association and Rugby football games in Victorian England.

This paper will suggest that soccer only became the global game we know today due to two crucial factors: its successful long struggle against the rugby code, and its adoption of professionalism in 1885. These two processes allowed soccer to eclipse rugby’s early Anglophone-centric partial globalisation and enabled it to transcend the control of its British originators, creating a sport that had a modern, meritocratic appeal to the non-English-speaking middle classes of Europe and South America.

The ‘beautiful game’ in the eye of the beholder

Today, most historians of soccer attribute its expansion around the world to what they believe to be its intrinsic qualities as ‘the beautiful game’. David Goldblatt, in his global history of football The Ball is Round, argues that 'football... offers a game in which individual brilliance and collective organisation are equally featured. ... The game's balance of physicality and artistry, of instantaneous reaction and complex considered tactics, is also rare’.

These observations may well ring true for aficionados of soccer, but supporters of other types of football also argue similar things for their sports. The aesthetics of sport, like beauty, are in the eye of the beholder.

More important for scholarly debate, such reasoning is ahistorical. It ignores the fact the it was rugby and not soccer which was initially the more popular sport in Victorian Britain. It fails to appreciate that up until the 1880s, the differences between the association and rugby codes of football were neither as clear nor as distinctive as they are today. And it also sidesteps the fact that rugby-type football remains, in significant regions of the world, more popular than soccer. Even if one accepts that the aesthetic argument is correct in our contemporary world, it cannot explain the historical reasons for soccer’s eclipse of rugby in the nineteenth century.

I want to suggest that explanations of soccer’s globalisation that are based on what are perceived to be its intrinsic qualities cannot provide an adequate historical explanation of the complex forces that enabled soccer to eclipse other forms of football to become the world game we know today. Instead, it argues that it was the English Football Association’s acceptance of professionalism is 1885 that laid the basis for it to overtake rugby in popularity and for its subsequent development as a mass spectator sport in Europe, South America and eventually the rest of the world.

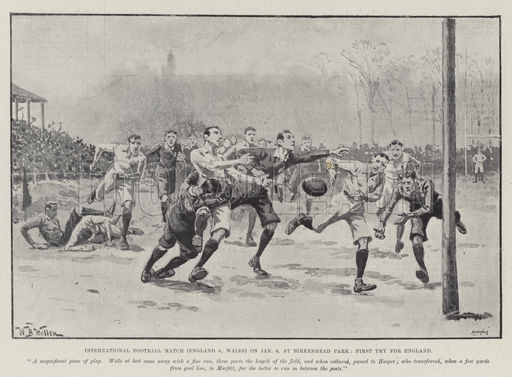

Rugby’s early ‘globalisation’

If the global expansion of soccer was not due to its perceived intrinsic merits, what did propel it around the world? By looking at the question in its broad historical context, we are led to a number of interesting questions regrading the relationship between soccer and other codes of football.

The first of these is the fact that until the mid-1880s, rugby was the more popular code of football in Britain. The formation of the Football Association (FA) in 1863 was a messy and incoherent affair. Indeed, given that the aim of those who sought to form an association was to create a unified set of rules to enable all adult football clubs to play each other, the process could be seen as a failure.

By 1880 rugby’s popularity among the industrial workers in northern England and south Wales had begun to change perceptions of the class composition of the two codes’ support. As The Field explained in January 1884, that ‘it is quite possible that the lower classes prefer watching a Rugby Union game, but that the Association rules find more favour in the eyes of the middle and upper classes is made amply evident by the crowds of respectable people that assemble [for major soccer matches] even in apathetic London’.

The popularity of rugby over soccer at this time should not be surprising. Tom Brown’s Schooldays, the 1857 novel about life at Rugby School by former pupil Thomas Hughes, had become a huge best-seller in Britain and throughout the English-speaking world. At the heart of the book was a thrilling description of the Rugby School version of football and as the influence of Muscular Christianity spread in the mid-nineteenth century, so too did rugby, the sport most associated with it.

Thanks to the cultural importance of Muscular Christianity to the British Empire, rugby soon become the hegemonic code of football in the ‘White Dominions’ of the British Empire. Even the distinctive form of football played in the Australian colony of Victoria, which became known as Australian rules football, was originally based on Rugby School’s rules. The Southern Rugby Union was formed in Australia in 1874. Matches between Australia and New Zealand sides began in 1884 and rugby tours to and from the British Isles started in 1888. The first British tour to South Africa took place in 1891. The Canadian Rugby Football Union was founded in 1882 and led the move from Rugby rules to a distinctively Canadian code of football.

Tom Brown was also best-seller in the United States and became the model for football in U.S. colleges. In November 1872 the New York World reprinted the book’s famous description of a football match as part of its coverage of the first-ever Yale-Columbia game. Teddy Roosevelt went so far as to assert that Tom Brown’s Schooldays was one of two books that every American boy should read. The Intercollegiate Football Association adopted the rules of the RFU with minor changes in 1876, and these laid the basis for the evolution of American football in the 1880s and beyond.

It is therefore the case that in the 1870s and 1880s rugby and its derivatives established itself as the dominant winter game in the English-speaking world due to the tremendous social and cultural cachet of rugby’s links with Muscular Christianity, particularly as popularised through Tom Brown’s Schooldays. The argument that soccer’s failure to become the major winter game of the United States can be attributed to ‘American Exceptionalism’, as argued most cogently by Andre Markovits and Steven Hellerman in their Offside: Soccer and American Exceptionalism, misunderstands how the international balance of forces between the football codes shifted in the early twentieth century. Far from America being ‘exceptional’ in its embrace of rugby-style football over soccer, it was conforming to the pattern of adoption of sport in the English-speaking world in the late nineteenth century.

In contrast, soccer had a much weaker international profile and cultural network at that time. It did not provide the same self-confident moral ideology for the Anglophone middle classes for whom rugby was an educational force. By the time that it had developed a strong international ideological profile in the early twentieth century, rugby-derived games were unchallenged as the winter sport of the English-speaking world (with the exception of much of England and Scotland which were dominated by professional soccer). This can be seen in the dates of the formation of governing bodies for the football codes. Outside of the British Isles, only Denmark and the Netherlands had created governing bodies for soccer before 1890.

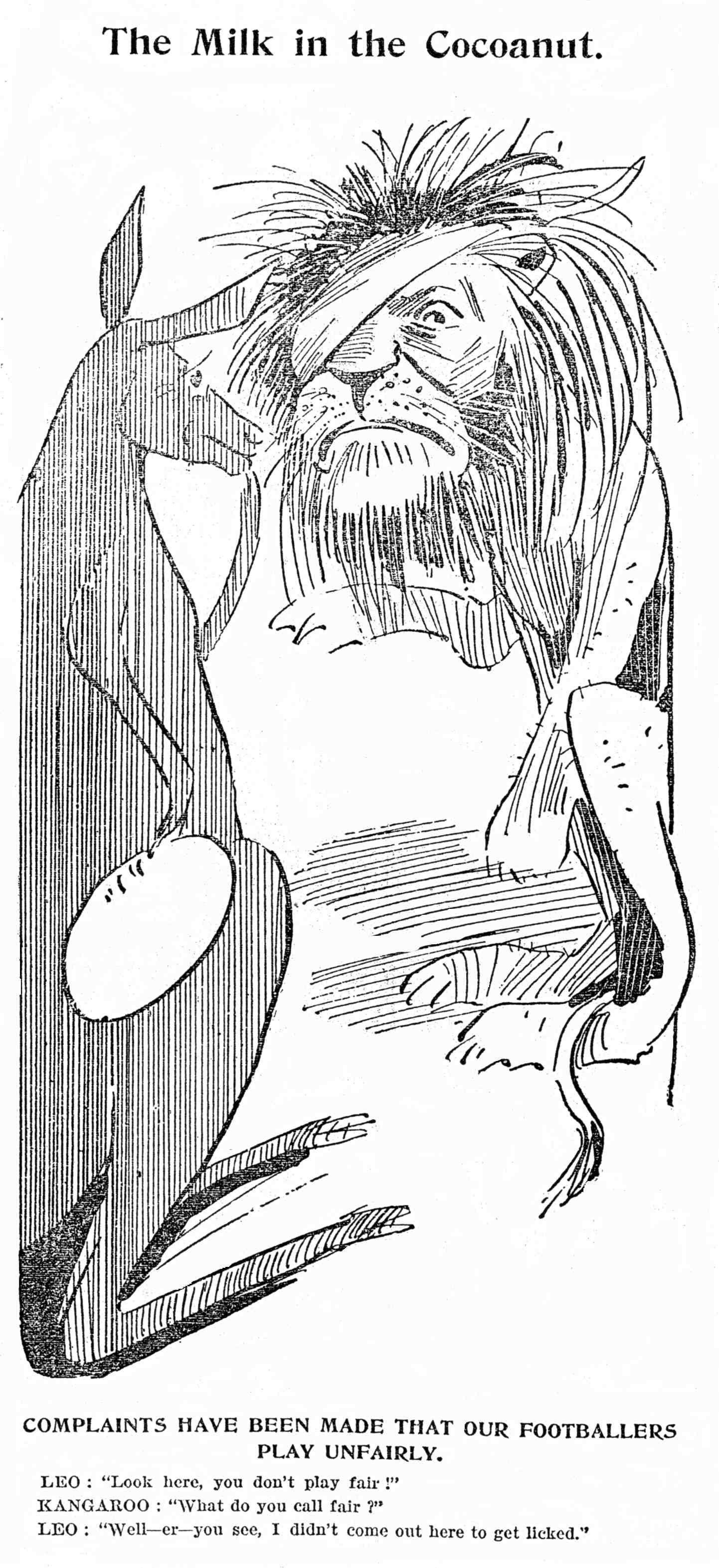

Yet in the same period governing bodies for rugby had been established in the British ‘Home’ nations, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa, as well as for the rugby-style codes in Australia and the United States. And, unlike soccer, international rugby matches were regularlyplayed across the hemispheres. By the end of the nineteenth century rugby and its derivatives had become the global game of the English-speaking world.

Professionalism in soccer and rugby

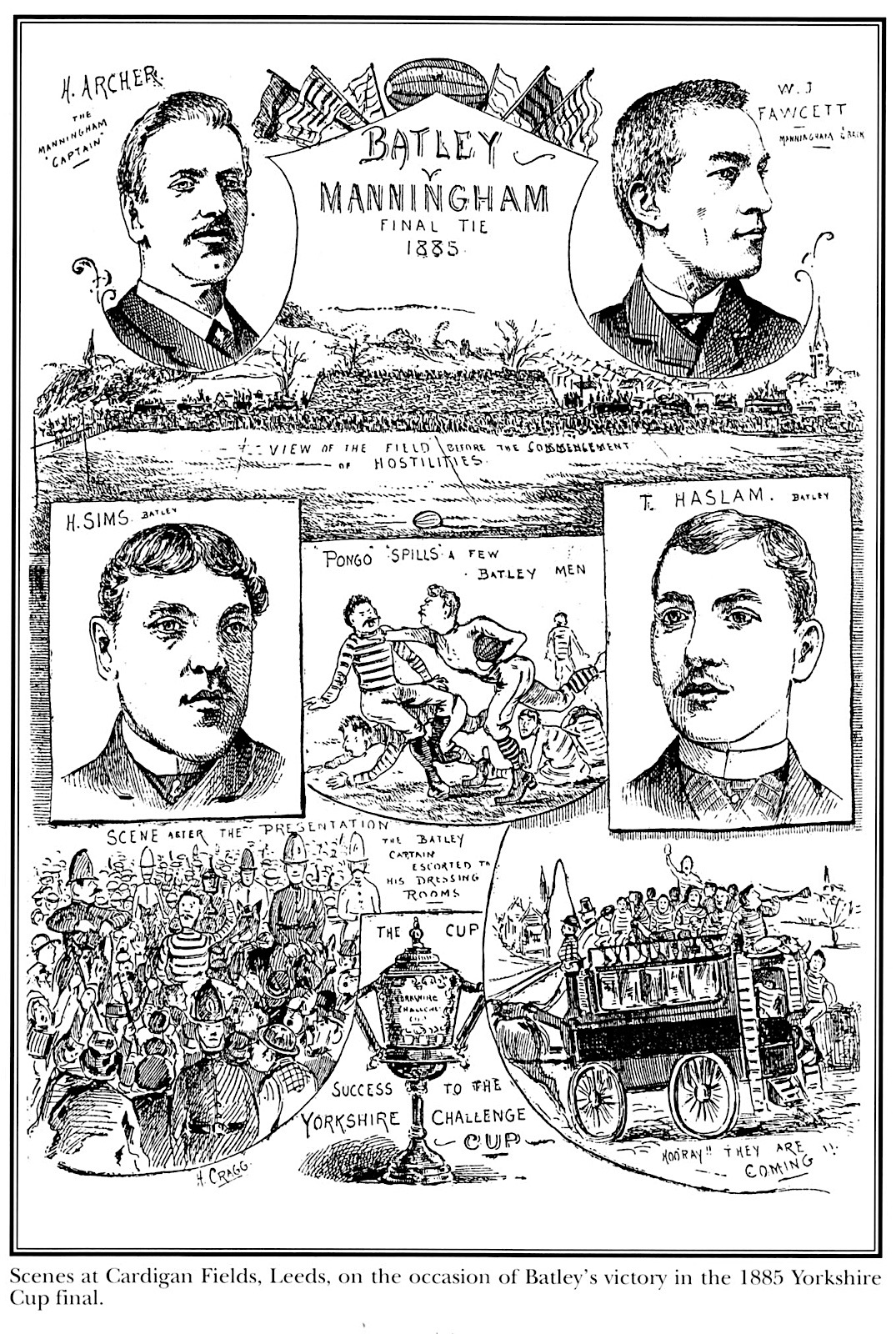

Soccer’s profile had begun to grow in the late 1870s when the F.A. Cup, which had started in 1871, became popular. In the industrial heartlands of Britain, both rugby and soccer began to evolve into commercial entertainment businesses during this period. Rumours spread that working-class players were being paid to play. In soccer, concern over payments to players came to a head in 1884, when Preston North End played Upton Park, a London club of middle-class ‘gentlemen’ in the FA Cup. The match was drawn but the Londoners protested to the FA that Preston had used professional players. Preston maintained that they had done nothing wrong and, supported by forty other clubs in the north and midlands, threatened to form a breakaway ‘British Football Association’. Faced with a potentially disastrous cleavage, the FA decided to compromise and in January 1885 voted to legalise professionalism. Although it could not be appreciated at the time, this decision would transform soccer.

The consequences of soccer’s move to open professionalism had a crucial impact on its rugby rival. Rugby was engaged in exactly the same debate about payments to players in the industrial regions of England and Wales, and the RFU was becoming increasingly alarmed that working-class players and spectators were driving out the middle classes.

So in October 1886 the RFU declared rugby to be an amateur sport, banning professionalism and outlawing all forms of payment, monetary or otherwise. The explicit aim was to curtail the influence of working-class players. The impetus for this draconian measure came in large part in reaction to soccer’s legalisation of professionalism, as was made clear by another future RFU president, Arthur Budd:

Only six months after the legitimisation of the bastard [of professionalism] we see two professional teams left to fight out the final [FA] cup tie. To what does this all end? Why this - gentlemen who play football once a week as a pastime will find themselves no match for men who give up their whole time and abilities to it.

He was correct in his prediction. Teams of working-class professional soccer players quickly eclipsed middle-class clubs such as the Royal Engineers and Old Etonians, with whom the leaders of rugby union closely identified. After 1883, no team composed of middle-class ‘gentlemen’ ever again reached the final of the F.A. Cup.

But the adoption of amateurism did not settle the issue of increasing working-class domination of rugby. Instead, it led to the outbreak of a civil war between the RFU and the predominantly working-class clubs in the industrial north of England that believed players should be entitled to ‘broken-time’ payments to compensate for time taken off work to play the game. In 1895 the conflict came to a head when the leading northern clubs, followed by the majority of other clubs in the region, broke away from the RFU and formed the Northern Rugby Football Union, which soon established a completely new form of the sport that became known as rugby league. The league version followed in soccer’s footsteps and allowed professionalism, but the union game cherished its exclusivity and rigorously defended the amateur ethos for another one hundred years until it abandoned its amateur principles in 1995.

Rugby’s civil war had left it exhausted - and soccer was the winner. Little more than a decade after rugby’s 1895 split the FA had over 7,500 affiliated clubs, roughly fifteen times the number of rugby clubs playing under either of rugby’s two tattered banners. Rugby could no longer counter the appeal of soccer, and public perceptions of rugby as a fractured sport at war with itself did nothing to help it win new supporters or players. By 1900, the balance of power between the two football codes was the opposite of what it had been in 1870.

Professionalism and sporting modernity

What impact did soccer’s legalisation of professionalism and its eclipse of rugby have on its international development?

The legalisation of professionalism decisively tilted the balance of power in soccer in favour of clubs composed of working-class professionals and organised on commercial lines. It opened the way for the widespread acceptance of league competitions throughout the game. In 1888 the Football League was formed, comprising the top northern and midlands professional sides. Within half a decade, almost every soccer club in Britain was part of a league competition.

Professionalism and the league system gave soccer the appearance of being a meritocracy. It could now claim to be a ‘career open to talents’, regardless of the social or educational background of the player. The introduction of leagues also meant that teams could be assessed objectively on the basis of their playing record rather than their social status.

Soccer therefore began to move towards a system of formal and objective regulation. This was in sharp contrast to amateurism’s informal social networks that were central to British middle-class male culture, in which the selection of players and the choice of opponents was often based on social status. Amateurism and the ‘code of the gentleman’ placed the informal understanding of the rules above their formal application, favouring the spirit rather than the letter of the law. Amateurism therefore privileged the insider who understood implicit unwritten conventions over the outsider whose understanding was based on the explicit written rules.

But in soccer, the opposite was now true. Professionalism brought continuous competition, precise measurement and the supplanting of personal relationships by the exigencies of the commercial market.

The leaders of professional soccer saw themselves as bringing the principles of science to the playing and organising of sport, as much as they did to their businesses. Their enthusiasm for cup and league competitions, and for the fullest competition between players and teams, reflected their belief that opportunities that should be available to them, free from social restrictions imposed from above. This conception of sport as an expression of the modern industrial meritocratic world, in which advancement was based on talent and skill, would be critical in making soccer so appealing to the world beyond Britain and its empire.

Professionalism meant that an external, objective set of rules for the governance of the game developed. Soccer was no longer based on social status and networks, but ultimately controlled by rules that were independent of whoever led the sport. Soccer’s relationship to Britain was now a conditional one.

Thus the men who formed FIFA in Paris in 1904 did not need the FA or the Football League for their legitimacy - soccer existed independently of its British administrators and British officials could do nothing to prevent FIFA’s formation. Moreover, the intense parochialism, and huge success, of British soccer meant that its leaders were largely uninterested in the spread of the game to Europe and therefore indifferent to the formation of FIFA or its work. The road was clear for soccer to become part of non-British and non-English-speaking cultures.

Soccer as a symbol of global modernity

The young men who took up soccer in Europe and South America in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were drawn largely from the technical and managerial middle classes, sharing similar backgrounds with British tradesmen, businessmen and engineers who established many of the first clubs outside of Britain.As Chris Young has described the situation in Germany, soccer found its most important constituency among ‘technicians, engineers, salesmen, teachers and journalists, who had previously found their personal and professional advancement blocked for lack of the right certificate or university examination’.This desire for a ‘career open to talent’ was precisely what soccer’s open structure offered, in contrast to amateur sports such as rugby union.

Almost all of those who founded soccer clubs outside of the English-speaking world had Anglophile sympathies, but their Anglophilia was part of a wider cosmopolitanism, as Pierre Lanfranchi has noted. Their admiration was for what they saw as liberal, modern capitalist values of the British legal and political system. This was the Anglophilia of Voltaire, who believed that Britain represented a modern liberal future, rather than the conservative Anglophilia of Baron de Coubertin, who admired the tradition and hierarchy of Britain (and was also a keen supporter of rugby and amateurism).

Residual controversy about soccer’s relationship to amateurism continued into the 1920s as the game in Europe and South America replicated the pattern of late-Victorian Britain and became a commercial mass spectator sport. Even though a number of national soccer associations remained nominally amateur until after World War Two - for example, West Germany’s Deutscher Fussball Bund did not officially recognise professionalism until 1963 - they never developed the elaborate systems of discipline and punishment that the British built to defend amateur principles.

FIFA self-consciously promoted a universalist philosophy for soccer. Five weeks before the outbreak of World War One, FIFA’s eleventh annual congress pledged itself to ‘support any action aiming to bring nations closer to each other and to substitute arbitration for violence’. In 1929 FIFA president Jules Rimet lauded soccer as an alternative to war, arguing that the game turned war-like emotions ‘into peaceful jousting in stadiums where their original violence is subject to the discipline of the game, fair and honest’. This sharply conflicted with prevailing attitudes to sport in Britain, whose soccer organisations left FIFA in 1920 in protest over its plans to arrange matches with teams from the central European nations defeated in World War One.

Perhaps the most illustrative example of how soccer’s modernist universalism triumphed over its British origins can be seen in Argentina. Argentinian soccer history has been without exception portrayed as a seamless story of upward progression after its introduction to the country by the British. But soccer became a mass spectator sport in Argentina only when it slipped out of the control of the local British community, which then embraced rugby as its premier sport.

In the 1890s, rugby and soccer were of equal status and popularity in Argentina. Its first soccer league began in 1891, and its championship was won seven times in the first decade by clubs that also played rugby.

As was the case elsewhere, British sport came to Argentina as part of the Victorian enthusiasm for Muscular Christianity. In 1882 Alexander Watson Hutton, who would become known as the ‘father of Argentinian football’, introduced football to South America’s oldest English school, St. Andrew's Scots School in Buenos Aires. But the catalyst for the rapid expansion of sport and especially soccer did not come from the English-speaking community but was a result of the 1898 Argentinian Ministry of Justice and Public Instruction decree that all schools, public or private, had to teach physical education and establish sports clubs for past and present pupils. Hundreds of clubs were formed in response and the sport began to be taken up by working-class Argentines, especially immigrants from Italy.

However, despite its status and high profile in Argentina, rugby did not participate in this transition to mass spectator sport. As working-class Argentinians and other non-British immigrants took up soccer, English-speaking sports clubs that played both games abandoned soccer in favour of rugby union’s amateur exclusivity. Even Alexander Watson Hutton’s son, Arnaldo, became a prominent rugby player. Rugby became a haven for those who wished to stay aloof from popular sport.

The same process of rugby union consciously choosing exclusivity over popularity can also be seen in Brazil. There, the rugby game was confined to elite social strata even more than in Argentina. Its major stronghold was the São Paulo Athletic Club, the club that was introduced to soccer by another ‘father of football’, Charles Miller. As in Argentina, the popularity of soccer among the masses proved to be unpalatable for the British-educated elite that ran the club and, despite winning São Paulo’s soccer championship in the first three years of its existence, it severed its soccer link in 1912 to focus on rugby.

The experience of Argentina and Brazil therefore suggests that, although football was introduced to South America by the British, they were not responsible for popularising it. Those who established soccer as the national sport of their respective countries were young men of the professional middle classes who were attracted to the modernity and openness of the sport.

This explanation of the complex rise of soccer outside of British influence dovetails with the recent work of South American historian Matthew Brown, who argues that British involvement in popularising soccer is overstated and, pointing to the cases of Peru, Colombia and Chile, that in many South American countries the game was introduced and popularised by young men from local elites. Their attraction to soccer was not its British links but the fact that it represented a modernity based on ‘commerce and aspirational lifestyles’ and their promotion of the game was not based on a relationship with Britain. Just as Christiane Eisenberg has pointed out in Germany, football for these Spanish-speaking young men ‘football was an indicator of their receptiveness to new things, in particular to economic modernity’.

Conclusion

The overwhelming global popularity of soccer today can have a distorting effect on our understanding of the historical process by which it achieved this position. Our familiarity with the game can lead to assumptions about its ‘naturalness’ or popularity that were not held by people at the time of its decisive development in the late nineteenth century. Hindsight can mistakenly allow us to imagine that sports were played or appreciated in the same way as they are today. Studying the history of ‘football’ as a generic category that includes all forms of the sport, can provide a much more rounded insight into the development of individual codes than can be found be studying each one individually.

This paper has therefore sought to put the development of soccer into the broader context of ‘football’ development in nineteenth century Britain and the wider world. Its underlying argument is that there was nothing inevitable or automatic about soccer’s rise to globalism. Its ascension to become the world’s most popular sport was not an unimpeded arc of progress. It was based on the defeat of its rugby rival and the eclipse of soccer’s British leaders by European and South American administrators - and both of these could not have been possible without soccer’s adoption of professionalism in 1885, which provided the basis for the meritocratic and modern outlook that would free the sport from the suffocating grip of British Muscular Christianity.

In short, soccer’s globalization required the defeat of the Anglo-Saxon attitudes upon which it was founded.