- - England play Wales tomorrow at Twickenham in rugby union's Six Nations tournament. This extract from A Social History of English Rugby Union describes the last time that England played a home game against Wales before rugby split apart in 1895.

For almost a decade the Welsh had dazzled and defeated their opponents through the brilliance of their backs and the innovation of their four three-quarters system. While England and the other nations still played with nine forwards and three three-quarters, the Welsh had moved a man out of the pack and into the three-quarter line, opening up play to create sweeping back line moves across the width of the pitch.

But now in January 1894, after years of debate and hesitation, England had decided to use the four three-quarters system. And the team they would use it against for the first time was none other than Wales.

This was no ordinary Welsh side. Captained by Arthur Gould, arguably the greatest Welsh centre of his or any other age, the side featured seven players from the Newport club, four of whom made up a mighty pack. Wales had carried off the Triple Crown in 1893 and were tipped to do the same this year. Even English reporters described them as ‘a side whose combination was never more perfect’.

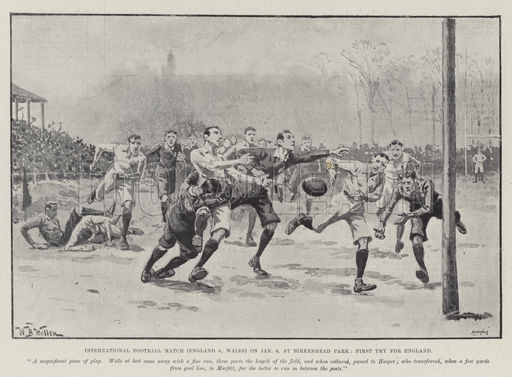

The match was the first and only international ever to be played on Merseyside, at the ground of Birkenhead Park. It had snowed on the Thursday before the match, necessitating straw being spread over the pitch to protect it from the elements. The temperature was approaching freezing when Bradford’s Jack Toothill kicked off at half past two, but the weather was quickly forgotten.

Despite intense forward pressure from the Welsh, it was England who scored first. Fly-half Cyril Wells made a break from his own quarter, got the ball to Geordie scrum-half Billy Taylor who passed back inside to West Hartlepool centre Sammy Morfitt to score between the posts on his debut. Captain Dicky Lockwood converted and England had the initiative. Just before half-time Charles Hooper caught a Welsh clearing kick on the full and made a mark, allowing Taylor to successfully kick for goal and record a rare four point ‘goal from a mark’. When the whistle blew for half-time England were surprisingly 9-0 ahead.

If the Welsh supporters who had travelled up for the match expected their side to turn the tables, they were to be disappointed. After the break, Taylor and Wells combined again to put Halifax’s Fred Firth in the clear. As he approached Wales full-back Billy Bancroft, he deftly chipped the ball over the Welshman, where it was regathered by Lockwood to score England’s second try. Lockwood again converted to make 14-0.

A few minutes later, Bramley forward Harry Bradshaw picked a loose ball from a scrum and barrelled his way over the line for another Lockwood-converted try. Then from a scrum Wells slipped the ball to Lockwood who broke through tired defenders before being brought down on the Welsh twenty-five, where Billy Taylor picked up the ball and scored in the corner, converting his own try from the touchline. Complete embarrassment was partially avoided when Newport scrum-half Fred Parfitt scored a consolation try just before the final whistle but at 24-3 the match, in the words of the Liverpool Mercury, ‘was not a beating, it was an annihilation’. It was England’s biggest win against the Welsh since their first meeting in 1881, when they had run in thirteen tries against a neophyte Welsh team.

More importantly, this was a very different sort of England team from that of 1881. Nine of the side came from clubs in the north of England. At least eight were manual workers. Only four players came from the traditional public-school based sides in the south. The captain, Dicky Lockwood, was an unskilled manual labourer from Heckmondwike. In this, the team was a vivid illustration of the way in which rugby had become a sport of the masses. No longer the preserve of the upper-middle classes, it was vigorously played and keenly watched by all sections of society, from the doctor at Harlequins to the docker at Hull Kingston Rovers.

But it was not to last.